Sometimes a name sticks.

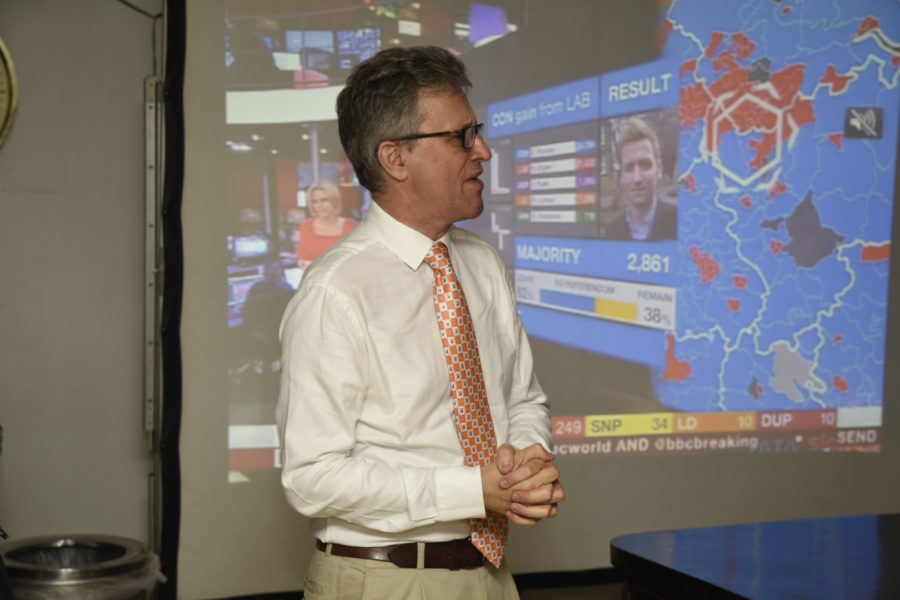

We’ve just had elections in Britain. As a general rule, British government officials should not show bias to any political party, because we serve our political leaders when they hold government office, and not in their political party role.

In the period between the announcement of elections and when they are held, while our political leaders conduct election campaigns, we follow specific guidance to civil servants. This reminds us we should not undertake activity that puts our impartiality into doubt, or allow public resources to be used for party political purposes, or compete with the election campaign for public attention.

Even if the formal guidance doesn’t say so, British civil servants think and talk of this practice as “purdah”, as in: “we are in purdah”. I’ve known the term for as long as I’ve been a civil servant, and it’s been in use since the late nineteenth century.

The word is of Persian origin and I guess it comes from the Mughal era. It means a “curtain” or “veil”, and describes the seclusion or separation of women from men. It’s still used here in India today: I read it last week in an article about Indian cricket. It’s one of many words that have made their way from India into the English language.

When I was researching this piece, I came across “Hobson Jobson”, the dictionary of Anglo-Indian expressions that was compiled in the late 19th century by two British officials who worked in India. They came up with 2,000 words and expressions, a lot of which we still use.

There are groups of words that have a lot of Indian origin. For example: words about clothes and materials, such as: pyjamas, khaki, chintz and pashmina. Some of them come and go with fashions (I’m not sure I could identify a piece of chintz if you gave it to me).

There are a lot of words relating to people and groups in society such as thug, pariah, guru and pandit. Some of these come from religion, and we too have our mantras. Avatar has been adopted by computer game creators.

We have many words for types of food and dishes, from fruits like mango and spices like ginger, to dishes of curry and chutney sauces. We know many words for food because of the large number of South Asian restaurants in Britain.

All languages absorb words from others. Glancing through the online edition of Hobson-Jobson, I was struck by the variety of the entries from many sources and not just from Sanskrit, the main language of ancient India. English is particularly acquisitive, maybe because our growth from the sixteenth century onwards was based on trade with many parts of the world. The trade was of culture and language as well as of goods and commodities.

The pace of absorption has quickened in the current era of global, digital communication. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which describes itself as “the definitive record of the English language” (note the word “record”: we are descriptive and not prescriptive about our language), adds roughly 500 words a year. Many come from digital media, and the numbers of new words makes the scope of “Hobson-Jobson” look limited in comparison.

I’ve become aware of the various expressions that Indians use which are unique to Indian English (which is one of 18 forms of English that my computer programme recognises). I’m still getting used to being introduced as a “Britisher”, changing my schedule to “pre-pone” meetings, or making an “air-dash” (usually to Delhi).

I suspect the OED will add more such Indian English expressions, and perhaps more words from those hybrid languages like “Hinglish”, as the next generation of young Indians (who I wrote about in March) communicate more on digital media.

The elections are over. We have a new government. For us Civil Servants, purdah – as we know it – is over. For the English language, I’m not sure there’s ever been a time when the language has been “in purdah”.