16th February 2017 London, UK

Researching user research

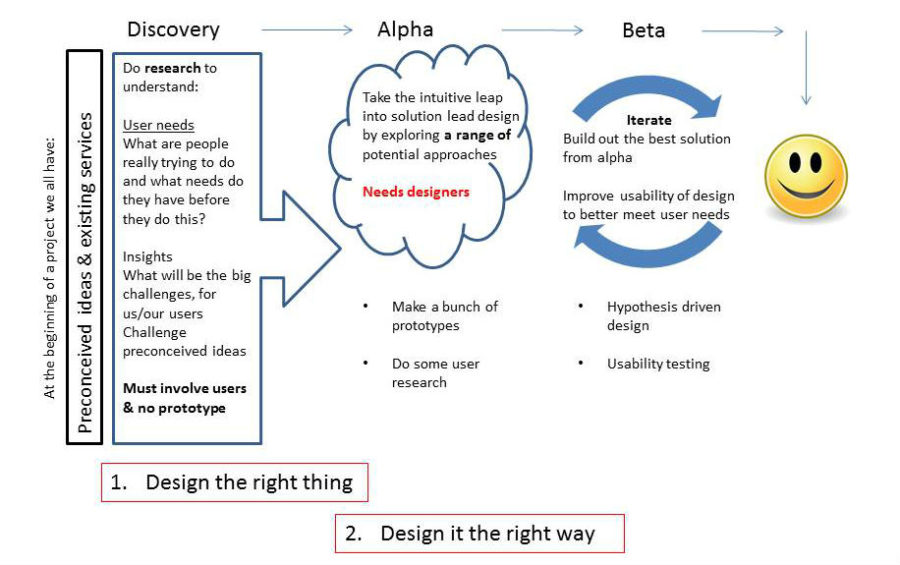

(User research in project phases – courtesy of Leisa Reichelt)

One of the first tasks I was given upon joining the Digital Transformation Unit within the Foreign Office was devising a strategy for user research. User research is at the heart of digitising government services. Everything we do should be designed with the user in mind to ensure services are easy to use and iterated to meet evolving needs.

This was an area I thought I knew about. Who doesn’t think about usability when developing a service? But I quickly learned that the extent to which the needs of each and every user are considered within government is more than I have ever encountered. With this in mind, I set off on a journey of discovery across government, researching the researchers and iterating my perception of user research along the way. I met user researchers from many different government departments. Some departments with large volumes of transactions being digitised have substantial user research resource, with teams of researchers, both internal and contractors. Some I spoke to are just starting their journey of digitising services and have smaller teams. Within the DTU all members of the team do user research as a core element of our job. But however large or small the team, in all cases the research is of paramount importance and evident in the user centric services. In addition to my discussions with other government departments, I completed the excellent user research training run by GDS.

So here are some of my favourite hints and tips that I picked up along the way:

- Don’t (just) ask users what they want! In the oft cited example given by Henry Ford talking about the development of the motor car, if you’d asked people what they wanted, they’d have said a faster horse. Instead, user research should primarily entail asking users what they’re trying to do and how they currently do it (and watch them do it). This will help establish the actual user need, which may be very different to what they initially say they want. It will also identify opportunities for improvement.

- Context is king. How, where and when users access a service will often have as much impact on their experience as who they are. In the Foreign Office many of our users are based overseas and our consulates are ideal places to speak to actual users accessing our services. These users could be holidaymakers, expats or business travellers, so meeting them in context gives a range of different experiences.

- Make testers stressed! This was a tip I picked up from a researcher at GDS and is a good example of the flexibility and pragmatism of this role, as it is actually the opposite of what is generally recommended as good practice which is to make participants feel relaxed and comfortable. It is not always possible or practical to test with real users at the point they are accessing the service. Many of our services are likely to be delivered to citizens in a high stress situation, and this is likely to influence their experience and abilities when using the service. To replicate this, make testers undertake a timed test in exam conditions prior to starting the user testing. This will raise their cortisol levels and they are more likely to make the same mistakes they would in real life when under stress. This approach should be used with caution and should be halted if the tester gets too stressed, however used carefully can be a great way of reproducing the context for the research.

- Take people (or show them videos). When sharing research with stakeholders it’s far more impactful to take them along or at least show videos. A written report is unlikely to have the same impact. But when sharing videos, if they are long, break them down into smaller clips if possible so viewers can choose the most relevant parts. If not, include timings on the video so viewers can scroll to the part they wish to view.

- Keep going until you hear the same thing over and over again. When I started I was anticipating being given numbers of users to speak to – or ratios depending on the volumes of customers expected to access the service but in reality, when speaking to researchers, when it comes to qualitative research there’s no magic number. The best advice I was given on numbers was to speak to as many people as it takes until you’re hearing the same things over again. This way you know there’s a user need.

This is just a handful of tips I picked up from an abundance of useful advice and information which has helped formulate the strategy and create a toolkit for performing user research. Perhaps the most useful thing I learned was to join the user research community who were incredibly generous in giving up their time and sharing their knowledge. I’m now excited to be putting all I’ve learned into practice as we continue to iterate our services.

It would be useful to have an app so that one had access to the local consulate or equivalent for making contact in the country being visited. This is assuming that contact would be necessary obtaining assistance for a lost passport.