19th March 2018 Skopje, North Macedonia

UK pulled Macedonia out of Brussels’ hostage and moved it to New York

Goran Mihajlovski is one of the journalists in Macedonia that has followed closely the relations between the UK and Macedonia since their early days. As part of marking the 25 years of relationship we asked Goran to give us his experience of the early 1990s and the British-Macedonian links.

Amb Garrett: How do you remember the establishment of bilateral relations between UK and Macedonia?

G Mihajlovski: In December 1993 I was a journalist in the political section of the daily paper Vecer. But, I recall bilateral relations between the United Kingdom and Macedonia beginning a year before the official start because the UK was deeply involved in solving the crisis after the dissolution of former Yugoslavia.

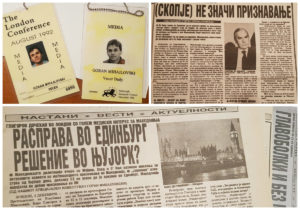

The United Kingdom played a key role in transferring the problem with the recognition of Macedonia from the then European Community into the United Nations. In June 1992 Portugal had chaired the EC Presidency. At that point the so-called Lisbon Declaration was adopted which stated that the 12 EC member-states would not recognise Macedonia as an independent country if its name contained the word ‘Macedonia.’ Fortunately, the EC Presidency was then handed on to Britain. Towards the end of August came the London Conference on Yugoslavia chaired by John Major. Besides addressing the war which was consuming Yugoslavia, that conference also paid some attention to the Macedonian question. Britain then appointed Ambassador Robin O’Neil as envoy responsible for Macedonia, who worked really hard. British diplomacy managed, at the Edinburgh Summit in December 1992 to annul the Lisbon Declaration and move the question of recognition of Macedonia to New York, to the UN. I recall that a few days before Edinburgh I interviewed Ambassador O’Neil in the Foreign Office where he welcomed me with a little flag of Macedonia (the then 16-ray flag) and spoke openly, deliberately using and reusing the name “Macedonia”. That came across clearly in my interview for Vecer. Then I was in Edinburgh where we Macedonians felt a certain relief because Britain had somehow managed to channel us towards the UN, extricating the dispute from getting stuck in the European Community. That was an extraordinary move that led to Macedonia’s membership in the UN only four months later, in April 1993.

Amb Garrett: What do you recall were the challenges for Macedonia at the time? And how have thy changed since?

Mihajlovski: I recall that I interviewed the first UK Ambassador Tony Milson in the Embassy’s old premises in the centre of Skopje. You were in the same building as the German Embassy. But, in the very moment I saw the United Kingdom coat of arms in the middle of Skopje and the flag, the plate with the royal coat of arms at the entrance to the building, I knew that we would make it. The fact that a member state of the European Community and a permanent UN Security Council member was opening an Embassy here, that meant they were determined to stay.

The challenges were huge. We were a country that was blocked by Greece. There was a blockade on the southern border and an embargo towards Serbia because of the sanctions caused by Milosevic’s role in the wars in Croatia and Bosnia & Herzegovina. We had no railway towards Bulgaria or Albania. We had long queues for petrol. And at the same time we had immense enthusiasm, great patriotism, the introduction of our own currency, new passports, the first matches for our new national football team…

I remember that when I landed at Gatwick with the new Macedonian passport, a few immigration officers gathered to take a look at it as if it were a miracle. I was lucky that I had journalistic accreditation so I had no problem to enter the country. I think that they put a stamp on a separate piece of paper; and then afterwards, until recognition, visas were also issued on a piece of paper. I evoke the memories of those days with excitement and thrill even today because in a way I was also part of history.

And where are we now? We are still far from what I would like us to be.

Amb Garrett: Diplomats tend to “big up” bilateral relationships. What do you, as an open, honest, transparent observer, see in the relationship between the UK and Macedonia? What are the real benefits to each side?

Mihajlovski: I don’t know if the United Kingdom has any benefit from us. But, we surely have. It is such a great treasure to have a friend that is a proven world player, a country from which we have learned democratic values, a country whose voice is heard everywhere. Sometimes we have been a little suspicious because history tells us of special relations between Britain and Greece; but when it comes to London’s official position, there is no messing about. There are no wicked games, nothing left unsaid, no surprises. We have learned that when London decides on something – then it will be done. Britain respects its decisions. From Edinburgh 1992 onwards, right up to the present day.

I won’t even start on the financial assistance Britain has given in the past 25 years. Those numbers are incredible and you know them better than me. The UK is one of the largest donors to Macedonia.

Amb Garrett: Is there something that links you personally to the UK?

Mihajlovski: In the summer of 1987 I spent three months in London. I was a student. At that time it was fashionable to go to London. We didn’t need visas with our Yugoslav passports. We went as if we wanted to study English; but in fact we worked in hotels, restaurants, fitness centres, boutiques… I wanted to be a doorman, to carry guests’ bags because there was a lot of tipping, but because I am a small guy they offered me work as a gardener in a hotel in Paddington. Can you imagine? I had no idea about gardening, let alone about gardening terms in English. But I managed. And I had great fun in that cosmopolitan surrounding, because by nature I am free-minded and curious. The owner of the hotel was a Cypriot Greek, the owner was Italian, the manager was English and the staff were from Spain and Finland. All of us, supposed to be studying the language. That summer I went to concerts of Madonna and David Bowie at Wembley. I could have died of joy that I was part of this world.

Then, as a successful gardener they transferred me to a more expensive hotel in North London, in Swiss Cottage. I earned good money there. But travelling by tube upset me. I was nostalgic for my little ‘fico’ car in Skopje, how cool that made me at college. And there I was, waiting in the underground – “next train in so and so minutes…” With the money I earned I bought a plane ticket to Ibiza along with my Spanish friends. The British then were discovering Ibiza as a party heaven… Britain was my open window to the world. I spent every last penny there. I came back to London without a single pound. Some Macedonian friends accommodated me for three days in Stockwell while I was waiting for the JAT flight, for which I had already bought a return ticket.

I feel so bad that we need visas for Britain. Plus the application process is so complex. I would otherwise go frequently for London, I would like my children to see my favourite places and the country that opened my views.

Amb Garrett: Which of the stereotypes about Britain and the British do you think is closest to the truth?

Mihajlovski: I don’t have stereotypes for anyone, including the British. Especially as while I lived there I saw that the stories about how cold the British are, how conceited, how fancy, that these stories were all fake. I like British humour. Sometimes that humour is so sophisticated I feel only the British understand it. But we also do understand it. My generation grew up with Monty Python; Allo, Allo; Fawlty Towers, Only Fools and Horses…

Amb Garrett: Who complains more about the weather – the British or Macedonians?

Mihajlovski: There is a big difference. The British talk about the weather for small talk. We complain about the weather. We suffer. Have you ever heard anyone in Britain being ‘killed by promaya’?