2nd June 2015 Skopje, North Macedonia

‘The Beginnings of that Freedome’

This is not a political slogan. It is the title of an exhibition that the UK Parliament is hosting in celebration of 800 years of Magna Carta. The exhibition commissioned nine artists to produce banners for the historic and beautiful Westminster Hall, celebrating key moments along our journey to modern democracy. If you are not able to visit it in person, you can see the exhibition online (http://bit.ly/1AHgjB1). (And by the way, the “freedome” of the title is no mistake – just an old way of spelling it.)

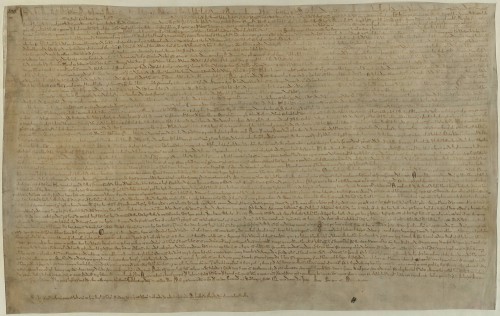

15 June marks 800 years since Magna Carta was drafted. Most of the clauses in Magna Carta related to mediaeval rights and customs. But some of it remains fundamental to British law today. The principle that a person awaiting trial is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty, can be traced back directly to Magna Carta. So can the principle of habeas corpus, under which the accused cannot be held indefinitely without trial. The concept of having a parliament as a means of obtaining the people’s consent also flowed from Magna Carta, as did the principle that nobody, even the King himself, is above the law.

Imagine that you are one of England’s barons, the most powerful men in the kingdom. You are forced to pay immense amounts in tax, imposed on you simply because the King wants more money to pay for his own projects. The barons were, understandably, rebelling and demanding limits to the King’s power. King John, a cruel and lecherous character, had alienated them not just with the excessive taxes but also by seizing their lands. A disastrous military campaign in 1214, which confirmed the loss of Normandy and other territories in France, forced the King on to the defensive. In a desperate bid to safeguard his position, he conceded the barons’ demands at Runnymede a place just west of London. But having agreed to Magna Carta, King John quickly repudiated it. The civil war began again.

Despite that bumpy start, Magna Carta effectively became the first written constitution. It was reissued in shorter versions in 1216, 1217 and 1225, during the reign of John’s son Henry III (1207-72). And for the next 200 years, kings reconfirmed it at the start of their reign. During the 17th-century struggles between Parliament and Charles I, Magna Carta assumed new significance as a written guarantee of political liberty. It was also a major inspiration for such great constitutional documents as the British Bill of Rights (1689) and the American Declaration of Independence (1776).

The provisions of Magna Carta covered the freedom of the Church, the rights of land owners and tenants, the liberties of towns and cities—it gave greater autonomy to the City of London: King John granted it the right to elect its own mayor—and reforms to law and justice. Magna Carta did not apply to women and unfree men (those without protected rights as freehold tenants), so affected perhaps only 10% of the population, but eventually it came to be seen as applying to everyone. One of its most famous provisions stated, ‘To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay right or justice’. For many legal commentators, that has long been the foundation stone of individual liberties under the law. In fact, it still exists in UK law as part of Edward I’s version of Magna Carta, which was made a statute in 1297.

There are many countries where the core principles of Magna Carta are severely challenged, through the unrestricted power of the executive, the state’s ability to curtail individual rights and lack of due process in trying individuals, through arbitrary detention, torture, and state-sponsored harassment of those who disagree with the government of the day.

The UK’s experience certainly doesn’t give us a magic key to resolve these and similar problems. But we are ready to draw on that experience in working with other countries to strengthen basic human rights and the principles of democracy. That can’t be done in a day. It takes time, huge effort and persistence. The responsibility lies with the people and also with the governments which need the confidence to be as transparent and accountable as possible.

In Macedonia, we have worked extensively in the areas of human rights and democracy – diversity, disability, basic human rights, freedom of expression, political dialogue, parliamentary democracy, implementation of the Ohrid Framework Agreement. We continue to work in many important areas of this portfolio and we will continue. Because it is important. Because we all need it, as individuals and societies.

We are using this year, the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, to mark and share Britain’s experience of democracy with others, andto invite debate about the relevance of its central messages today. Because freedom, democracy and open dialogue never go out of fashion.

Charles Garrett, British Ambassador to Macedonia

Photo credit: Photo of a copy of the original edition of Magna Carta, for display by the British Library. http://bit.ly/1Bj1KZZ