4th May 2021 Vienna, Austria

Diplomatic lessons 7, Berlin 2002-2006: work isn’t everything

One of the first mornings of my career break, as I dropped the kids off at school, I ran into an Embassy colleague. “How the mighty have fallen,” he said. I couldn’t think of a witty response.

In 2002, after working full-time for 23 years, I took four years of what the Foreign Office called “special unpaid leave”, or SUPL1 to look after my children, aged 8 and 10. It turned out to be the best four years of my working life. Looking back, it may not have helped my career. But I did OK; and my life was immeasurably better as a result.

Being at home, I cooked for the family daily. No-one died.

A key goal of stopping work for four years was so that their mum, Pamela, could go back to full-time work. In fact, she took over my job in the British Embassy in Berlin as Counsellor EU & Economic (see previous blog in this series). She had been working part-time for years but didn’t feel comfortable with the idea of both of us working full-time in jobs with lots of evening engagements or with the juggling of childcare that would entail.

19 years ago, this job swap caused some interest: as someone said, “it’s like reality TV, only it’s real, and it’s not on TV.” An editor at the Financial Times said “man at home: rich source of copy”. She asked if I’d like to write an article about how it felt. The result was published in the FT of 9 May 2003.

The FT sent a photographer to illustrate their 2003 piece. Result: good photos

The most fundamental change to my life from taking four years out of the office to look after the children was that I developed a stronger, life-long bond with them than ever could have happened otherwise. I’m not saying I discovered some mystic relationship key. But more hours together, and me having more responsibility for them for a substantial chunk of time, brought us closer. For that alone, I was eternally grateful to have had the opportunity to step outside the office routine.

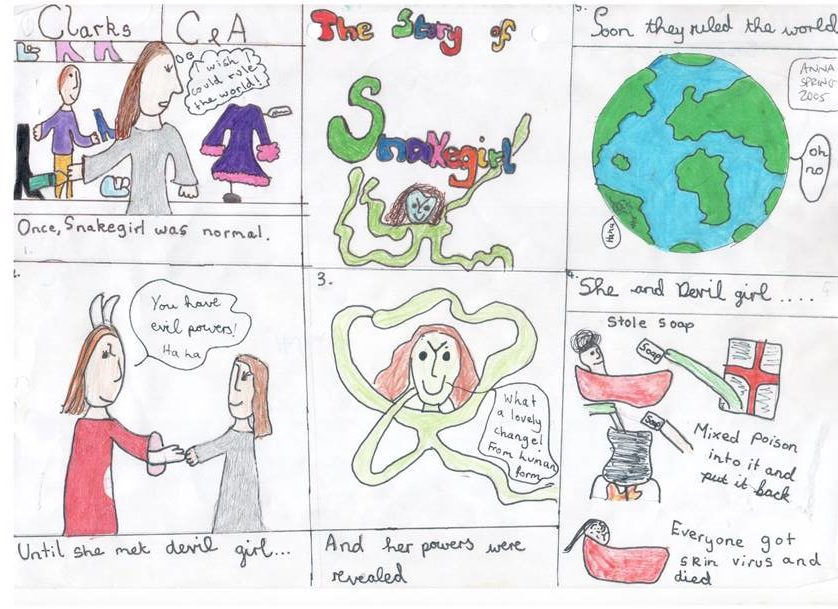

Being at home I could appreciate the artistic talent of my daughter, eg “Snakegirl”

Getting out of the office also freed up time to do other things. Again, I’m not claiming any special insight or achievement here. But I wrote a complete novel, my Berlin thriller Blood Summit; wrote several dozen articles for the FT, the Boston Globe and other newspapers; and made new friends, including members of one of the world’s premier walking groups. This, too, was life-changing.

Numerous people told me it would be difficult to re-enter the Foreign Office after SUPL. “You should gain a qualification,” a well-meaning senior colleague told me. “Learn skills. Do something the Office can gauge, or value. Otherwise your time out is just a black hole.” Others told me to enjoy it while I could. The latter was closer to the approach I adopted, although I did learn lots about writing and journalism.

Despite the warnings, I was bemused to find when I started applying for jobs on promotion in London, for which I had felt 100% qualified four years earlier at the end of my time as Counsellor EU & Economic, that I was not even shortlisted. I explored jobs in my grade; still nothing. At last a wise colleague who knew me a bit called. “I wondered if you might like to apply for one of the most unusual jobs in the Foreign Office,” she said. “It’s the Head of the Overseas Territories Department.” I’ll write about that in my next post.

What was the impact on my career of stopping work for four years? As millions of women who have tried it can tell you, evidence that taking a career break to bring up children accelerates your career progression is not abundant. But my career has been respectable and satisfying; and the non-work gains, immeasurable.

What lesson can you draw from this? A speaker at a London Business School course I attended shortly before these events put it well. Statistically speaking, he said, only two of the twenty people in the room would reach the pinnacle of the organisation. “The rest of you, indeed all of you,” he said, “should have something else in your life that gives you intense satisfaction, in addition to your careers.”

Excellent advice.

*

The previous posts in this series are:

– Diplomatic lessons 1, 1979-83: Don’t judge a book by its cover

– Diplomatic lessons 2, 1983-87: Languages change everything

– Diplomatic lessons 3, 1987-91: go for the hard jobs

– Diplomatic lessons 4, 1991-95: have a plan, and break it

– Diplomatic lessons 5, 1995-98: make a difference

– Diplomatic lessons 6, 1998-2002: pendulums

(1) Some US readers have said this expression makes it sound as if I had been suspended without pay pending disciplinary action. This was not in fact the case.