23rd October 2014 Sofia, Bulgaria

Memories from Sofia

by Prof. Richard Crampton

In his story for the #100UKBG series, the renowned British historian Professor Richard Crampton, author of the book “A Concise History of Bulgaria”, shares memories of his frequent visits to Sofia over the years.

Complement with a video of the lecture “British Perceptions of Bulgaria – Some Personal and Professional Reflections”, which Prof. Crampton gave on 27 June 2014 at the British Ambassador’s Residence in Sofia, as part of the celebrations for the 100-year anniversary of the historical building, and photos of the event.

“It was a traditional Apteka at the corner of two streets just behind the Grand Hotel Sofia. In addition to its huge, multicoloured glass jars of chemicals, it had a wonderful array of weighting scales, pestel and mortars, and was lined with beautiful cabinets each drawer of which was labelled with some mystical formula. It was like something from a by-gone age and, if I could, I made sure that western friends visiting Sofia for the first time should see it.” – Prof. Richard Crampton

I first went to Bulgaria in the spring 1967 as a young, naïve, graduate student. A few days after I left Sofia an irate mob attacked the British embassy; not despair at my departure, I fear, more whipped-up anger at Britain’s policy over the Six Day War. During my visit two young Bulgarian history graduate students were assigned to look after me. One was Zina Markova who went on to write briliant books on the history of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, but who was later sadly stricken down by disease. The other was Andrei Pantev whom, I am honoured to say, has remained a friend, and although we seldom see one another my admiration for him as a historian and a figure in contemporary Bulgarian public life is enormous.

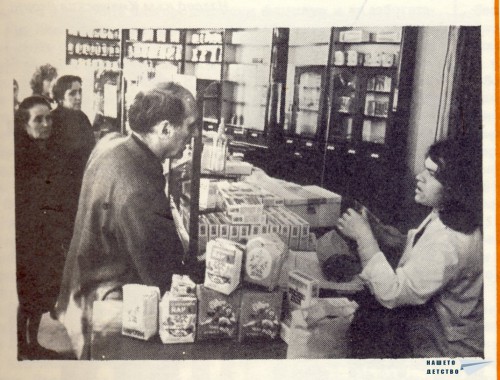

Sofia in 1967 was only beginning to edge into a modern urban society. Traces of the former society were still to be seen, for example, in the women who went every day with enamel basins to collect yogurt from a local dairy, or took flour to one of the few remaining communal bakeries to make their bread.

That first visit also included a weekend away visiting Plovdiv, Gabrovo, and Tûrnovo. One of my abiding memories of that weekend is stopping somewhere in the mountains between Sofia and Plovdiv, and the road was not what it is today, and talking to a local shepherd. I don’t remember what he said but he was dressed in a kalpak and sheep-skin jacket and could have been taken from the pages of a travelogue of the 1870s. The old Bulgaria showed up again occasionally in subsequent visits. On one such visit I was staying the Academy of Sciences guesthouse, not an exercise to be undertaken lightly, during the 9th September public holidays. Having little else to do I wandered down what was then Boulevard Chapaev towards the centre of town and passing a building site heard a guzla being played. Sitting on a pile of breeze blocks was the player clothed almost as archaically as the mountain shepherd previously encountered. A less wholesome reversion to the past, I suppose, is the reappearance in the streets of Sofia of the dancing bears.

In the autumn of 1974 my wife and our two sons, then aged five and two, came with me to Sofia for a couple of months. Our elder son attended the American school out in Knyazhevo. The fees were way beyond the limited pocket of a young academic so to pay our son’s way my wife gave art classes. We were lucky in that a young British diplomat with responsibilty for cultural relations was assigned to look after us if anything went amiss, and Edward Clay and his wife Anne have remained life-long friends. One of my wife’s strongest memories, in addition to grappling with the idosycracies of the cursive in Cyrillic, is of the yogurt. In the mid-1970s yogurt was relatively little known in the British Isles, still less the unsweetened or unflavoured variety. Those wonderful glass jars of plain yogurt were wonderful and we still wonder whether yogurt in a plastic carton tastes quite as good.

And glass jars reminds of another of my favourite spots in by-gone Sofia which lasted, I think, utnil beyond government times. It was a traditional Apteka at the corner of two streets just behind the Grand Hotel Sofia. In addition to its huge, multicoloured glass jars of chemicals, it had a wonderful array of weighting scales, pestel and mortars, and was lined with beautiful cabinets each drawer of which was labelled with some mystical formula. It was like something from a by-gone age and, if I could, I made sure that western friends visiting Sofia for the first time should see it.

My visits to Sofia were mainly professional. My main research and teaching interests were in the history of the twentieth century in Europe, particularly Eastern Europe and the Balkans. On many occasions personal anecdotes enriched my knowledge of Europe’s history. I will give just three examples.

In the late 1970s Andrei Pantev invited me to lunch in what was then The Czech Club. (Whether it still exists I do know.) Andrei said he wanted me to meet one of the waiters. The latter turned out to be a man of quite advanced years who had worked in the Club for almost all his adult life. At Andrei’s prompting he told me of one particularly incident which I often used to relate to my students as an example of the moral ambiguity that history sometimes poses. The waiter told us that in second world war the Club was frequented by German officers. One of the latter persistently refused to settle his accounts which was not only rude but a real burden on the waiters who had to make good the deficit from their own meagre wages. Eventually exasperated by this, our waiter reported the matter to a senior German officer. The following day the offender was posted to the eastern front. After finishing his story, the waiter became wistful and said, “You know, I have had that man on my conscience ever since.”

In the mid-1980s I was having a pleasant lunch with a Bulgarian historian of great prominence. We were talking about the “regenerative process”, that is the forcing of Slav names and other measures taken against Bulgaria’s ethnic Turkish minority. My friend said one fear in Bulgarian ruling circles was that Turkey would do to Bulgaria what it had to Cyprus a decade earlier, that is, annex territory inhabited largely by ethnic Turks. I questioned whether that was possible given that Turkey and Bulgaria belonged the two great opposing alliances, NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and that neither Washington or Moscow would want to risk war over such an issue. “Oh!”, said my friend, “the Warsaw Pact won’t exist in five year’s time.” I was stunned. But I remembered that conversation when the Warsaw Pact did disolve five or six years later.

The final story dates from a few years after that conversation. It was in September or October 1989 that together with an English friend and colleague who specialises in modern Greek history, I attended a historical conference in Sofia. “Attended” might be a generous description of our conduct because we put in very few appearances at the NDK and the historians’ conference. Far more interesting was it to walk the streets and sit in the bars of Sofia absorbing the electrifying atmosphere of what we now know were the final days of communist rule. One indication of the changes in the air was that many buildings previously closed to visitors were now open. These included the large mosque near what was then Lenin Square, and also the nearby synagogue. We were looking around the latter when a lady of mature years appeared from an office and asked if she could help us. I explained that we were two English historians with a special interest in the Balkans and were delighted to be able to visit the synagogue for the rist time, and this was accepted without demur. I then added that I knew a Bulgarian Jew in England who had worked for many years in the Bulgarian section of the BBC. She asked me what his name was and I told her. Her face assumed a quizzical look and she asked if he came from Sofia. I said no, that he was in fact from the south, from Stara Zagora. The woman’s jaw dropped and her eyes filled with tears: “Sammy”, she cried, “It’s Sammy”. Their parents had been the closest of friends and the two children had been constantly in and out of each others’ homes. They had been all-but brother and sister. And yet, this was the first the lady had heard of Sammy since he walked out of Bulgaria in 1944.