22nd January 2021 Belgrade, Serbia

Counting COVID

This is the first blogcast I have recorded for several weeks. This is mainly because I had to travel to the UK for family reasons – a journey that was a story in itself. But there is another reason too. I have been spending my evenings doing an online training course.

Diplomacy is a career of life-long learning, whether that is languages, local history, international treaties or law, or the science behind topical foreign policy priorities. At the moment that means, for example, improving our understanding of coronavirus infection transmission rates and of carbon emissions.

The course I am doing is highly relevant to both. It’s a ‘masterclass’ for senior British public servants on the use of data in policy making, and it is presented by a series of eminent statisticians, many of whom now find themselves unexpectedly to be household names.

I love numbers. So, I will admit that I am enjoying being able to look at numbers in a way that goes way beyond my Embassy budget, important as that is.

The data studies for my training course though, aren’t the only data I am looking at.

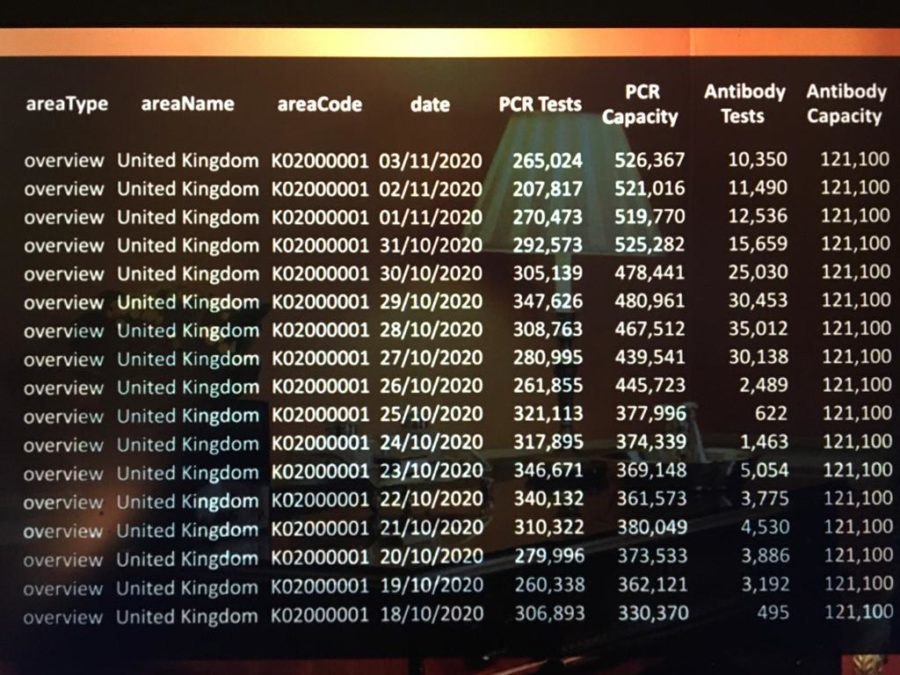

As a diplomat, I never anticipated that graphs and statistical tables would be the first and last thing I looked at every day. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed that, not just for me, not just for diplomats of course, but for very many people.

As for diplomats, we anxiously watch the daily figures in our home countries, thinking of families and friends as we do so. Professionally, we pay very close attention to the figures and trends in our host countries which affect the staff and families of our own diplomatic missions and the people we work with across the countries in which we are serving.

We look at infection, hospitalisation and testing rates, and at the numbers of recorded, and so-called excess deaths. In the UK we also talk a lot about the ‘R’ number, a figure calculated using massive computing power to show how many other people somebody with COVID-19 is likely to infect.

Here in Serbia, you can follow the mortality figure, that is the number of confirmed COVID cases that result in death, a sharp daily reminder that every number is a human being.

I look every day at graphs published in the Financial Times where you can compare interactive data from around the world. It’s important though to look behind the published numbers and remember that countries may not always be comparing like for like. Is public health guidance on the need for a COVID test the same? Do identical rules apply for recording a death as caused by COVID? How do the thresholds for admitting a person to hospital compare? There are many variables that mean we cannot always be sure that we are comparing like for like.

Quite rightly too, Governments around the world face scrutiny about the accuracy, timeliness and completeness of the data upon which daily policy decisions about public health are based.

Public health measures themselves are often being set in numerical terms: the number of people who can meet indoors, the number allowed to attend a place of worship, the permitted size of a football crowd – the number of days in self isolation or waiting for test results. Such numbers may not always be a precise science, but they are easy to remember and help keep us all safer by reducing risk.

In the UK in the final months of 2020, we had a system of tiered measures, set according to the local level of infection and pressure on local health services. Back in my home village in the UK in December I found myself first in Tier 2 and then, overnight, in the top tier – Tier 4. In Serbia too different towns have introduced local emergency situations as numbers of COVID cases fluctuate.

In both countries, however, we have seen that, no sooner do you apply local measures in one place, than the numbers rise elsewhere. It’s not easy to get ahead of the virus.

Without simple public health measures like washing hands, covering our faces, and distancing ourselves from other people, the spread of the virus would be much worse. But it seems that such precautions are not enough to stem it.

One particular challenge is mutation and the emergence of even more infectious strains. Scientists in laboratories across the UK have cooperated through cogconsortium.uk to map, or sequence, the genetic material of over 200,000 different variants of the COVID-19 coronavirus. (Incidentally, that number is apparently almost as many COVID-19 coronavirus genomes mapped by UK scientists as around the rest of the world combined.) These statistics are sobering reading.

Now though we also have some new, more optimistic statistics to follow: the effectiveness of vaccines and the rates of vaccination.

Scientists globally have worked with extraordinary speed and skill to develop and test a range of vaccines. Medical regulators too have worked exceptionally quickly to study and analyse vaccine trial results and approve use of vaccines they consider to be safe and effective.

The UK’s Royal Statistical Society recently held a competition for its ‘international number of the year’. The winning number was 332.

That is the number of days between scientists first publishing the genetic sequence of the COVID-19 coronavirus and the first dose of an approved vaccination being given less than a year later. Developing a new vaccine normally takes many years, so this is a very impressive number indeed. It was though, only because so much research had already been done on other coronaviruses by scientists at Oxford University and elsewhere that it was possible to move so quickly on this one.

In the UK our regulatory authority, the MHRA, has approved the use of the Pfizer-BioNTech, AstraZeneca and Moderna vaccines. All showed high levels of effectiveness and safety in trial results that had been published and peer reviewed.

The website of Oxford University’s ‘Vaccine Knowledge Project’ vk.ovg.ox.ac.uk/covid-19-vaccines is full of useful facts and figures. It also explains how vaccines are developed, the difference between the different vaccines approved for use in the UK and so on. It even lets me see the probability of me having a sore arm after a Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination as compared with an AstraZeneca one.

These two vaccines – whose storage temperatures, impressive protection rates and comparative costs are already well-known statistics – are now in use in the UK, having already been tested upon a total of 67, 000 people.

Over 4 million people in the UK, including HM The Queen and her husband HRH The Duke of Edinburgh, have received at least the first of their two doses of COVID vaccine. Similar to other countries, vaccines are being offered first to older people, and to people whose health conditions or healthcare roles put them at greater risk of serious illness.

The British Government hopes to vaccinate 13 million people by the middle of February.

But that is just the start. It is only by vaccinating a large proportion of a country’s population that we will make a significant difference to the coronavirus spread. It isn’t exactly clear yet what that proportion might be.

As a point of comparison though, I believe that over 90% of small children in the UK and Serbia are vaccinated against measles – a disease that used to be a significant cause of child mortality and which is exceptionality infectious.

Of course, it is not enough to vaccinate the population of a single country or group of countries.

I look forward to the first deliveries of vaccines through the COVAX facility that is designed to ensure fair access to vaccines for countries around the world. I’m really proud that the UK has dedicated a very significant amount of funding to this initiative, some £548 million, and helped to raise something around a total of one billion US dollars from international donors.

To vary my reading diet, as well as looking at the world of numbers, I have been reading about the history of vaccination. Many years ago, at school in the UK I had learned about Edward Jenner, an 18th century doctor who noticed that milkmaids who had been exposed to cowpox did not become ill with the much more serious disease smallpox.

But only recently I also learnt that in the early 18th century, a distinguished woman called Lady Mary Wortley Montagu who was married to a British ambassador, had already brought to the UK the practice of variolation, or immunisation by exposure to smallpox itself, as practised in the Ottoman Empire. I’d be interested to know whether it was also used in Belgrade in those days.

Modern vaccination is very much safer than those long ago days when mothers would risk exposing their children to a small dose of the deadly smallpox rather than leave them open to the greater risk of catching it unprepared.

I’m certainly looking forward to having a coronavirus vaccination in due course. Injections don’t always agree with me. But I know that a few days of feeling a bit under the weather is a far better alternative than catching a serious, maybe life-threatening disease.

In the meantime, I will be celebrating each time that I hear that a friend or colleagues’ father or mother has been vaccinated, or that someone with an underlying health condition has been protected. I will celebrate each time that I read that developers of a new vaccine have published full, peer reviewed, test results, and each time that I hear that a new vaccine has been approved by internationally respected authorities for use. Such transparency and such endorsement is essential for public trust.

I look forward to reading data that millions more doses of vaccine have been produced, more countries supplied, and more people vaccinated, wherever they are in the world. Fighting COVID-19 should not be a competition for influence. This has to be a common struggle in a common cause.

I hope too that, as vaccination programmes are rolled out, it will not be too long before the daily charts and graphs also start to show sustained falling trends of COVID-19 infection, hospitalisation and death.

2020 was a very tough year for so many people. Let’s hope 2021 is a better one.