12th December 2014

Romanian Revolution through British Eyes/ Bernard Marshall: ‘Two days of the Romanian Christmas Revolution in December 1989’ (Chapter I)

‘December 21st – 10.30 am on Palace Square, Bucharest

“Please move back “, said the tall Securitate official.

Three diplomats moved back a few steps onto the now empty square.

“I asked you to move – please move back “, he ordered again – in surprisingly refined and clear English. He was wearing a long black leather coat and black astrakhan fur hat.

“Why?”, I replied. I then pointed over his shoulder to some students now shouting very loudly a hundred meters away, and asked

“Look, what’s going on over there?”

“Nothing special of any importance“, he said.

Reacting with undiplomatic and rising frustration, I responded: “Then I feel very sorry for your country!”

He paused and looking at me with astonishing calm and a trace of a smile, and said: “Yes, we have beautiful people, like in your country too!”

This exchange took place on Palace Square. Fifteen minutes earlier Romania’s Stalinist dictator had given what was to be his final public address on this spot. For me, my short and meaningful exchange above encapsulated much about Romania and its fascinating people.

Trapped for so long in a police state, the attitude of this once dreaded Securitate official framed much of what I saw over the next two days: unforgettable brave and sometimes tragic actions by students armed only with hope and ideals; mixed reactions by those in authority; the unbelievable power of hope; the unstoppable surge of the human spirit. And the power of young people and ideals whose time had come to escape the police state – a condition which they and their parents had endured for unusual reasons, far too long.

That late December ’89 all eyes of the world were now on Romania and its dictator – to see how it would respond to the surge of freedom that had just swept across the Eastern Bloc. The Embassies tried their best to keep up with (and ahead) of this drama. We and the American Embassy sent two diplomats on December 15th to Timișoara just the day before the first shots were fired in that city. Their mission was to re-establish contact with the dissident Hungarian born and Protestant Bishop Laszlo Tokes whom the authorities wished to move. The diplomats managed to get to his church. But just when they saw the Bishop on the steps, they were confronted by two Securitate officials who forcefully escorted them back to the airport. As they left the church, an old lady in the small crowd of parishioners then assembled outside whispered to our diplomats, “you must come back tomorrow and see what happens”. They missed the uprising there by a day. (A previous ambassador famously had sent a report that spring to the Foreign Office predicting notwithstanding the changes taking place elsewhere that Ceausescu would only be removed once his own health failed him).

08.15 am

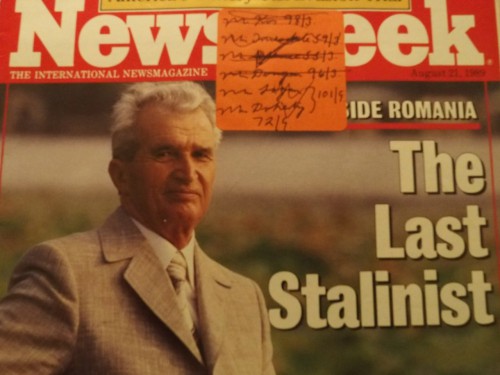

According to my diary of the time, Eleanor, my cheerful and chubby cook arrived late that Thursday morning, at 8.15am. She told me that all the factory workers had been ordered to go to Piața Victoriei now for the President’s address that morning. She looked worried, and had been held up by a crowd at the Hungarian Embassy on her way in. Even now she was wary of saying more. She rightly assumed my flat was “bugged”. We had a policeman with a Russian machine gun at the entrance to our diplomatic block. But she always made her feelings clear with gestures. I recall her reaction to a Newsweek Magazine of 21 August 1989. Ceausescu stared down defiantly from the cover under the bold heading, “Inside Romania -The last Stalinist”. I always left the magazine face up on the coffee table. And when I returned from the Embassy, I always saw it face down!

All eyes at our Embassy were firmly fixed on the President’s next move that warm December morning. At our regular 9am meeting held in “the quiet room “ on the first floor, our Ambassador calmly assigned us monitoring tasks for the President’s rally. Mine as First Secretary was to make the first patrol on the streets from 10.00 to 11.30am, to assess the mood, and get as close to Palace Square as possible. The Dictator now back from Iran was due to deliver this speech after ten, direct and live on TV “to his people” who were now lining up on Bucharest’s Palace Square.

The previous days had been filled with warm and beautiful blue skies. A smart young official I knew at the Ministry of Agriculture had the day before used this chance to tell me, with a friendly smile “Yes, all the good weather now comes from the West; let us hope it continues and we get more!” It was good that everyone found it easier to move around, without snow and ice to hinder them.

10.00 am

Under this warm blue sky I strode out eagerly, through the tall Embassy gates into Strada Jules Michelet. The Romanian Security Guards in their grey uniforms saluted, smiling and trying hard to look “unconcerned”. Huge concern had of course been building all over Romania during the last five days, despite a news blackout about ‘a massacre in Timișoara’.

Turning left on the main street I crossed to the other side of Boulevard Magheru to find a side approach to the Square. A few yards in, I could just see the heads of the people now assembled on Palace Square. Quickening my pace I approached a white wooden barrier barring my entrance. I showed my diplomatic ID pass to the two policemen. As expected, they shook their heads firmly and smiling: would not let me pass. I looked down another side road but that was also blocked.

Heading back into the main boulevard I noticed very few people walking about in this main street of Bucharest. But this was not unusual. The shops were empty. People were not allowed to congregate in numbers more than three. Everything had an air of being controlled – including talking to foreigners.

Still I needed to try and assess the mood of people outside the square, so I popped into what represented a cafe. The place was quite full with around 12-15 young students who had their heads down and were talking very quietly. A radio perched on a shelf up behind the bar was playing. The Dictator had started speaking from Palace Square just a few hundred metres away. None of the students were listening. So I asked the barman who was speaking on the radio. He smiled and shrugged his shoulders and did not answer me. The students who heard me avoided looking up. Having arrived five months earlier I was used to this. I had little chance of usefully getting cutting through to them, even though the atmosphere in this cafe with its half dozen tables of three and four students now huddled close in quiet conversation was just that “little bit more” unusual today. With the little radio carrying the old leader’s crackling and croaking harsh tone, the barman seemed the only one prepared to comment – with his smile.

10.40 am

Dispirited, I slowly wandered up along the largely deserted Boulevard towards the Embassy. It was around 10.40am. I was wondering how best to report “nothing”, and about to turn into Jules Michelet, at the top of Magheru, when a crowd of young men and boys raced past me throwing down rally placards, as they ran down the steps of the entrance to the metro. I asked an old lady dodging these boys what was happening. She shrugged her shoulders and said the meeting must have finished and perhaps they were keen to get back home. I carried on unconcerned to the Embassy. Just then, two colleagues came running out of the gates towards me. One of them called out : “Come quick, let’s get to the Square – they’ve just pulled the plug on Ceausescu!”.

Three of us now raced back down Magheru and onto Palace Square. This time no policeman to stop us. And to my astonishment the place was now quite deserted! We moved across the right side of the Square to the Athenee Palace hotel where a number of police were gathered.

10.45 am

This is the moment we came across my tall Securitate officer, with his long black leather coat and smart astrakhan fur hat. It was when we glimpsed sight of our first student demonstration. Maybe up to a hundred and fifty students were chanting and jeering at an entrance to this Square. And they were being held by thin line of police, back to the side of Hotel Bucharest.

This was perhaps the starting point of the student demonstrations and uprising in Bucharest, where the Dictator had been jeered and forced to abandon the platform on this very Square, fifteen minutes ago. We now took the advice of the Securitate officer and moved away to get a closer look elsewhere of “what was going on”.

As we moved, a line of around thirty helmeted soldiers led by a ponderously fat and old platoon commander in a heavy great coat, and a barking German Alsatian on a long lead, marched double pace across the middle of the square and towards the students.

We moved around the back of the Athenee Palace. Standing right in the middle of the road there were six young thin and nervous looking police (or soldiers?) with truncheons dangling behind long riot shields. We walked by them as they stood waiting anxiously back to back, forming a small circle in that road. Now we heard glass breaking. Students cheered louder as they broke the glass entrance to the hotel eighty meters in front of us. Flags and placards lying in the street had been burnt. In our side street we saw a green military canvas truck. Students were now being snatched one by one, and dragged away struggling. We saw two or three students in jeans being swung high by their hands and feet onto the back of the open canvas truck. Two lines of police at the hotel were being pushed back. But when reinforced they pushed forward again jostling with the jeering students calling “Timișoara”. It seemed the police were gaining the upper hand, despite more sounds of crashing glass. This group of young people were being pushed back around the corner, and out of my sight. Anxious to find out what else might be happening, and having lost my two colleagues, I decided to go back. I passed by that tight circle of young soldiers again, standing back to back on the deserted street, quietly waiting their turn.

11.45 am

Back at the Embassy. Smiling anxiously, Ambassador Michael Atkinson called a meeting as soon as we returned. It was clear that a serious uprising was now underway in the city. It was only an hour since TV had shown an incredulous and stiff faced Ceausescu being hurried quickly off the balcony platform. Seeing him on the balcony of the Communist Party Headquarters retreating had been enough. The Embassy felt the dam had broken; the moment when brave souls could suddenly jeer in front of a Dictator realising “Look, the Emperor has no clothes!’

Now this vital spark had been ignited in Bucharest, five days after Timișoara. The question was: would the silent people and workers in heavily controlled Bucharest and other towns seeing that drama on television now come out onto the streets? Would the regime be too strong and snuff out this new people energy? It was our job to assess and report. But many of us in the Embassy also felt involved at a personal level. We had got to know the Romanians.

03.00 pm

By early afternoon we were in standby mode at our desks. The Ambassador and two political colleagues were busy reporting morning events by “flash” (the highest priority) telegram to London. At around 03.00 pm I was called out to meet a group of students who on their way to Magheru stopped at our now firmly closed Embassy gates. They asked excitedly if we might help them with perhaps some loudspeakers or megaphones they could use. I called the Ambassador, who advising me that we had to “remain strictly neutral”, came down and offered his regrets, before they moved on. (A junior Foreign Office Minister had already in fact probably “sunk our boat” by appealing on BBC World Service just after “Timișoara’ for the Romanians to rid themselves of their Dictator).

03.30 pm

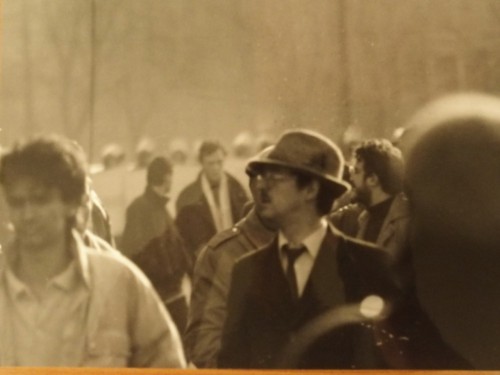

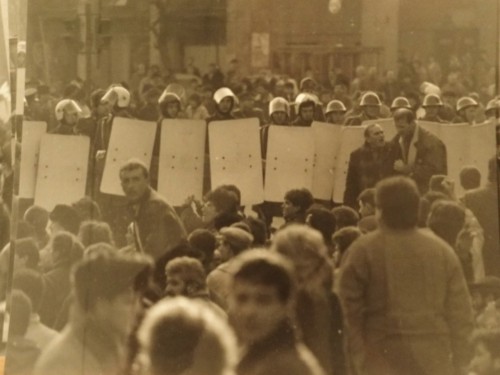

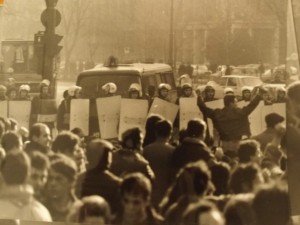

With no fresh reports from the streets, a colleague and I ventured out to see what was now happening. We joined a stream of students passing our gates and onto Magheru. We could see a group of 50 police with riot shields marching up Magheru towards us. We found ourselves backing onto Piața Romană and herded in with a large group of about 200 or more students and protestors all loudly shouting ‘Jos Ceaușescu!’ (Down with…). One or two lines of police were standing in front of blue police vans. Armoured personnel carriers (APCs) joined later with green helmeted soldiers leaning out their turrets. A helicopter circled low and the students jeered louder. When it left, protestors at the front sat down and chanted in unison to the bemused soldiers, “All Europe is with us /Come and join us/We were once soldiers too/Come and join us/All Europe is with us“.

(…)We all joined in with the cheerful chanting. Some people around us wanted to shake hands. All these demonstrators seemed to be aged in their twenties and thirties. One of two of the very few black and white photos taken by an Embassy colleague at the time captures the heady and expectant atmosphere. It was a special moment, with all of us repeating the rhythmic “Ti-mi-șoa-ra”, “Li-ber-ta-te” and “Jos-Cea-u-șes-cu’”.

I recognised only one person – one of the few aged over forty – in the crowd. We smiled and laughed at each other. He was ‘our tailor” with his corner shop near the Embassy. And he was now living up to his rebel reputation which he had gained playing the “banned BBC” World Service on his radio whenever we visited his shop. Piața Romană seemed to have an almost a carnival like atmosphere now, with serious pushing taking place only now and then.

04.15 pm

But it was getting dark and a grey sky was descending. We decided to leave Piața Romană. This protest group was growing bigger and in fact becoming more tense and impatient with the standoff. There were some bangs (sounding like blanks or warning stun guns) coming from the main Square, which added to the tension. A bus with more riot police arrived. The students banged on the sides of this bus. Two small armoured personnel carriers moved forward to the front of the police lines as the protestors were getting rowdier. We did not want to stay anymore or become blocked in this Piața.

I walked a few minutes along Strada Dumbrava Roșie towards my flat to see to my friends at the nearby Austrian Embassy. I heard crackling at Parcul Ion Voicu and looking up saw yellow tracer paths of bullets or fireworks in the sky behind. Over Viennese coffee I told the Deputy Head of Mission what we knew. (They all had been “too busy” to leave their Embassy?). I then walked back in the dark to our Embassy. A homely yellow ground light lit up the large oak tree behind our gate. It also lit up the tidy green strip of grass beneath my commercial section windows, and bathed the whole of the Embassy in gentle light.

05.30 pm

The Ambassador had sent most of our Romanian staff home to see their families were safe. They had looked worried all grouped together in the waiting room that morning. Some seemed confused and unable to grasp what was happening. The Ambassador calmly called us to another meeting. We needed to get information from other Embassies but the telephone lines appeared to be cut. Our Ambassador said he had been unable to phone the American Ambassador “Punch” Green Jr. Richard and I leapt at the chance to go out on foot to re-establish contact with the Americans. Their Embassy was situated just down the road at the other end of Magheru and to the side of the InterContinental hotel and main University. It was normally a seven minute walk.

Deciding to avoid the Police blocks on the main blvd., we picked our way along the side streets and passed the English Church. The Ambassador had been there first thing that morning talking to his friend and US counterpart “Punch”, the once retired businessman, about the upcoming Christmas services. They both noticed factory crowds they saw being dropped off by bus just outside all heading for the rally. Three minutes into our walk, we heard a heavy rumble and squeaking of metal getting louder and coming towards us in the dark. Panicking for some reason thinking that it might be a tank (the carnival atmosphere had now all but disappeared as we got increasingly serious reports), we both jumped at the same time into a doorway. We waited and peering out saw instead a large police truck with a water cannon on top, trundling across the road with all its bells clanging. A student was somehow standing on the roof and banging a large hammer down on the metal. Not wishing to be trapped in this alley, we changed course and headed into the wide main blvd. linking our two Embassies. Magheru was now fantastically lit. The normally dim lights had been turned “full on”. It felt and looked very strange. No traffic, just stationery groups and lines of police and soldiers and a dozen APC’s. It seemed like a stage set for a brightly lit film. There were ten or more military and police vehicles stood still in wide empty spaces. We turned left down towards the University, and at the first barrier showed our diplomatic pass to police, who let us through.

Ahead were many more police with soldiers in bigger numbers, three or four lines deep backed up by APCs and they were stretched out across the road by the InterContinental hotel. I heard both sharp and muffled sounds. I thought I heard the sound of gunfire and saw soldiers with rifles aimed high above the heads of protesters.

As the US Embassy was just to the left of all this, we moved forward quickly. Staring hard ahead and at the backs of these lines of police and soldiers about a hundred yards away we could clearly see and hear the mass of protesting students. Then quite suddenly, we noticed some women just to our right. Looking down and against the side of our pavement we saw eight or nine young people lying on their backs. The old women in black and holding red handkerchiefs to their faces were crying over these bodies. There were no signs of injury. But they were clearly dead and closely heaped together. One, a man with straggly blonde hair and thick cream woolen turtle pullover in blue jeans was closest. I think I remember seeing a girl with brown hair amongst these tragically still bodies. The shock was so sudden. Totally stunned it was a few moments before I managed to speak and say to my colleague (who also did not speak then) that we had better head straight back.

We ran much of the way back to the Embassy and up the entrance stairs. The UK-based security officer opened the inner electronic glass door. As I passed by his glass security booth his phone rang. Quickly picking it up he asked me what to do with the caller – a London news station wanting to know what was happening. Although I did not usually take media enquiries (…), I instinctively knew what I had to do. “I will take it”, I said and still breathless described the scene we had just witnessed. The lady at the London end of the phone asked what I thought would happen next. I replied, still emotional, “All I know is that there are eight or nine very brave students who are dead out there. Anything is possible”. Putting the phone down I felt relieved. And fortunate I had done a small duty for those unknown students lying in the street half a mile away. They were no longer unknown.

06.00 pm

Apparently both of us still white with shock, then went to tell the Ambassador. This was the first evidence of casualties in Bucharest. The news was out and could no longer be erased or covered up by the regime. My phone conversation was relayed on a BBC home radio station at 05.00 pm, and later that night on the BBC World Service. This news was heard that afternoon by my friends in London and even reached an American friend, who stopped her car in Chicago when she heard me. (A plaque was later placed on the wall near the church on Magheru naming these brave students where they fell. It records they had been run down by a military truck, and were the first casualties in Bucharest).

As more news kept coming in of bigger crowds, and shooting which could be heard across the centre, it was clear a full scale uprising was underway six hours after that rally. (And not a single Western journalist now there to photograph or record it).

After being unable to go on foot the Americans, telephone connections started working again. To our surprise calls to London and with the media were getting through. Everyone was busy on the phones. I went out again to see my Austrian friends to recover a bit. Returning to the Embassy, the Ambassador still at his desk and suggested around 08.00 pm that we might go home. I had no appetite that moment to see what was now happening outside. A colleague invited me to his home for a bite to eat. A few of us now drove in our cars through empty side streets without hindrance. I don’t think we had eaten lunch, so the imported treat of Heinz baked beans on toast and pies tasted wonderful and normal. The Austrians joined us. We put on a video trying to return us to routine and a sense of normality. (…) An Embassy attaché then phoned us to say she could see fires by the InterContinental hotel and hear the demonstration from her home. Thinking of going back to my own home, and having recovered my energy after midnight now, I said would take a quick look at the University area again to see what was happening.

08.15 pm

In my red Mercedes I drove the mile back into town with the Austrians avoiding Magheru, and took the side route past the English Church and straight to the front of the American Embassy. I parked on Strada Batieștei, showed my pass to the policeman standing by the US Embassy makeshift barrier, and saw this huge demonstration taking place. It was happening at the same spot we had seen earlier, on Magheru alongside the InterContinental hotel, about 150 metres away from me now. It was around 12.30am.

The noise was terrific. Sheets and pillars of flames burst up in front of students from tires and debris and four or more cars and trucks on fire. The noise of this riot – shouting and jeering in unison – was frightening. It was completely mesmerising and not quite real, despite what I had seen. But it was real. It seemed the students were trying to surge forward and each time a volley of shots rang out. I assumed this was over the heads of demonstrators, but I could not see exactly. This was then followed by individual gunfire and more waves of jeering and shouting. The fires were burning intensely, 10-15 feet high in places with a glow that reached me and a dozen onlookers standing under a big tree, a few feet from the US Embassy .

Amidst all this tumult, a young Romanian now said to me, his face glowing from the fires, “ All this because of one man . And a man who cannot even speak Romanian properly. Or any foreign language”. This comment about Ceausescu’s literacy at this time jarred. But it seemed important to this Romanian in the midst of all this action. He told me he was an engineer. Meanwhile the students seemed to be thinning out and moving back . The gunfire and noise of students started decreasing. This was around 1.30am and from where I was standing, the police appeared to be moving forward and breaking up the students into smaller pockets. It looked like the battle taking place since early afternoon on University Square, was lost . I decided to go back to my car and drive to my home in Strada Alecu Russo. The side streets were empty and quiet. I got back to my diplomatic block of flats in 5 minutes. I made two cups of coffee and took them downstairs at 2am to the two “Milimen”. Looking friendly but bemused I indicated to them I hoped they would not use their machine guns on the students! Now from inside my bedroom I could hear the sound of gunshots and bangs from the centre. It was not easy to sleep. The day long sound of chanting and jeering crowds and rolling engine noises would not stop ringing in my ears.’ To be continued

(I cannot confirm all happened exactly as I have written above. It is based on two pages of my 1989 diary, a few documents and a vivid memory of that time 25 years ago).

By Bernard Marshall

Embassy staff between 1989 and 1991

Disclaimer: This account does not represent the view of the Her Majesty’s British Government, but is a personal recollection of the December 1989 events in Romania.