15th March 2016

The Screwtape Letters

On 14-16 March we are celebrating Northern Ireland. One of Northern Ireland’s best-known, and best-loved writers is Clive Staples Lewis, who was born in Belfast in 1898.

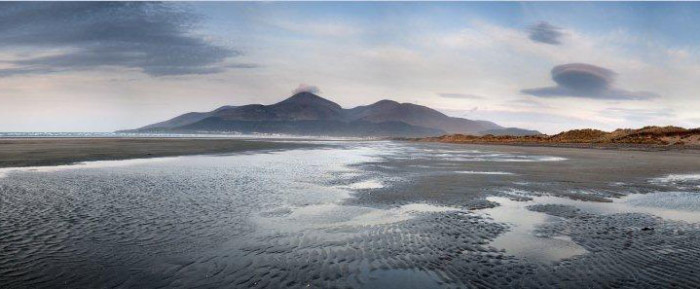

His most famous works are the Narnia series, following the adventures of the Pevensie children (based on a group of children who were evacuated to stay with him during the Second World War) and inspired by The Mountains of Mourne. That series has a strong Christian theme running through it, but Lewis claimed: “it all began with images; a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn’t anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord.”

One of his earliest works was The Screwtape Letters, a collection of letters from a senior devil (Screwtape) advising his young (and not very competent) nephew Wormwood on how to corrupt a human (only referred to as “The Patient”). This book, published in 1942 (and dedicated to J R R Tolkien, one of Lewis’ great friends at Oxford and a fellow member of the Inklings literary group), turns many of our preconceptions of religion on their head by approaching them from the opposite direction. Thus Screwtape recommends that The Patient, if he must pray, should do so in “parrot-like” fashion, whilst concentrating on some image rather than the ideals behind it. There are other gems of advice: “all extremes are to be encouraged”, “jargon, not argument, is your best ally”, “the safest road to hell is the gradual one”.

One of his earliest works was The Screwtape Letters, a collection of letters from a senior devil (Screwtape) advising his young (and not very competent) nephew Wormwood on how to corrupt a human (only referred to as “The Patient”). This book, published in 1942 (and dedicated to J R R Tolkien, one of Lewis’ great friends at Oxford and a fellow member of the Inklings literary group), turns many of our preconceptions of religion on their head by approaching them from the opposite direction. Thus Screwtape recommends that The Patient, if he must pray, should do so in “parrot-like” fashion, whilst concentrating on some image rather than the ideals behind it. There are other gems of advice: “all extremes are to be encouraged”, “jargon, not argument, is your best ally”, “the safest road to hell is the gradual one”.

The letters have a sly humour running through them. Screwtape refers to “The Father” and “The Enemy” – although not as we would imagine them. He gives his protégé advice on the temptations of lust, gluttony, pride and false humility. Eventually the plans are for naught as the Patient is killed and goes to Heaven. And Wormwood pays the ultimate price at the hands of his “increasingly and ravenously affectionate uncle, Screwtape”.

Lewis found The Screwtape Letters unpleasant to write, and refused to write a sequel (there was a short essay in 1959). But he left us with an amusing, but withering, satire on human nature – worth a read even today.