In her book “The Mighty and the Almighty”, Madeline Albright asked rhetorically:“Why can’t we just keep religion out of foreign policy?”. She responded: “we can’t and shouldn’t. Religion is a large part of what motivates people and shapes their views of justice and right behaviour. It must be taken into account”. The last fortnight has demonstrated this with clarity. Arguably, issues around faith and religion are more important to the work of diplomacy than at any time since the 17thcentury.

The outrage across the Muslim world to the film “The Innocence of Muslims” is understandable. Even if some responses have been terribly misplaced or, worse, wilfully manipulated – the violence, the targeting of diplomats, the deliberate misunderstanding of democratic norms of free speech – it is clear that in this networked world, a single act by a madman or extremist provocateur can be flashed around the world in minutes, and we all have to deal with the consequences. How we do so is in large part a task for leaders, religious and secular, including diplomats.

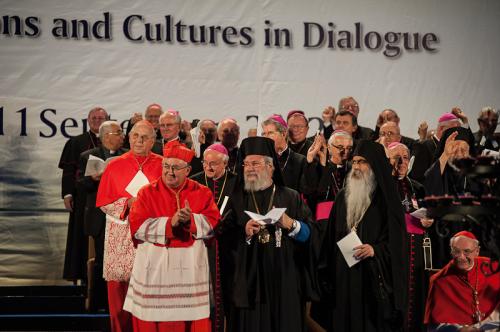

And that is where two extraordinary events of the last fortnight come in. The first was the meeting of dialogue and prayer organised in Sarajevo by the Sant’Egidio Community. On the 20th anniversary of the outbreak of war in Bosnia, Sant’Egidio brought religious and political leaders to Sarajevo to reflect, to talk, and to pray. The key message was that in this modern and globalised world, in which diversity is the norm not the exception, religions have a role in forging peace and helping different communities live together.

The other event, of course, was Pope Benedict’s extraordinary visit to Lebanon. The Pope’s messages were clear and stark: fundamentalism is a negation of religion; authentic faith does not lead to death; shared freedom, tolerance and creativity, must be the fruit of the Arab Spring; if you want peace, respect life; dialogue across the religious divide is the key to peaceful coexistence. In other words, whilst religion is an element in the problem, it also needs to be part of the solution. As diplomats, we cannot ignore that.

If diplomats have a tool, it is dialogue. If authentic religious leaders have instruments, they are their words and prayers. Andrea Riccardi, founder of Sant’Egidio, has asked since the Sarajevo meeting: “Can dialogue really change relations between peoples?”. The interim answer appears to be: well, without dialogue, there is no chance, even if dialogue alone is not sufficient. That’s the challenge.