18th March 2013

Doing What Works – the Data Revolution

This month in the UK we launched the ‘What Works’ Network – new centres of evidence to help ensure better decisions across £200 billion of public service spending. It’s the first time a government has set up such a model. The video launch at NESTA is well worth a look.

The Network consists of two existing centres of excellence – the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Educational Endowment Foundation – plus four new independent institutions in the areas of crime prevention, active and independent ageing, local economic growth, and effective early intervention (with young people to reduce social problems).

The role of the Network is to gather and assess the most robust evidence so as to inform policy and improve services at local and national level.

It might sound like a statement of the bleeding obvious. How could you not base policy on evidence? What else would you base it on? Hasn’t looking at what works and learning from our mistakes been our guiding principle for centuries, from Isaac Newton standing on the shoulders of giants, to Florence Nightingale pioneering the use of measurement to guide medical interventions? To the point where our technological advances are granting us 5 additional hours of life every day of our lives, and giving our children a 25% chance of living to a 100.

But Geoff Mulgan’s NESTA blog reminds us of John Maynard Keynes’ observation that governments don’t always find it easy to have all the evidence: it can make decision-making much harder.

This is where the OECD can help. Every day it compares hundreds of economic and social policies across Member countries and beyond to show what works best, where, and hopefully why: better evidence makes better policy.

For example, Germany has learnt from the UK and US in setting up their Teach First Deutschland programme. In the UK we’ve learned a lot from Australia’s welfare-to-work programme, where it seems the biggest difference in outcomes is probably down to the amount of money the Australians have been able to invest. It’s about much more than money though. In terms of education, Finland and the UK spend about the same amount per child, but the OECD evidence is that Finland’s results are better. We need to understand the evidence and work out why.

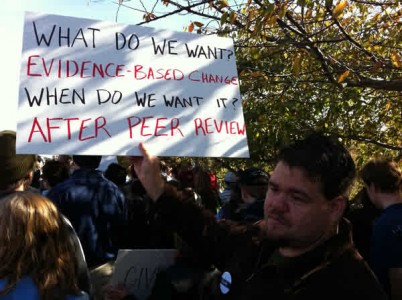

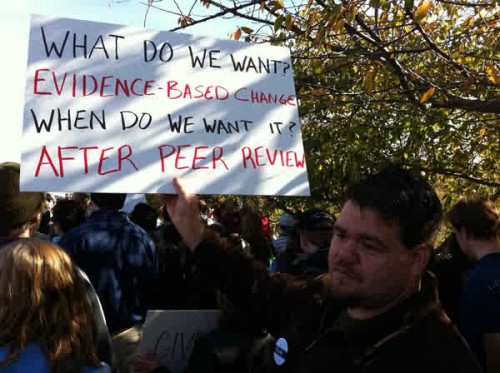

The What Works approach comes at an interesting moment. Not least because the current economic situation means that every penny of taxpayer’s money needs to count. We are recognising that good policy needs to be evidence-based. Data is becoming sexy.

First, open data. In the UK and elsewhere there has been a big push to make public data freely available in order to improve public services and boost growth, not least through the creation of Tim Berners-Lee and Professor Nigel Shadbolt’s Open Data Institute. David Willetts reiterated his goal at the OECD to see all publicly-funded research made available to the public. The OECD has already decided to go down the route of making all its data free and openly accessible, and is undertaking work on the opportunities and challenges of open government data, building on its 2008 Recommendation on Public Sector Information.

Second, the Big Data phenomenon. This is the harnessing of computing power to manipulate the vast quantities of data we are gathering in our digital age and use it to improve policy. I heard a fascinating example of the potential of Big Data in relation to the UK’s National Health Service. Crunching through the world’s biggest health database – decades of symptoms, diagnoses, treatments and outcomes for virtually every person in the country – could help us make dramatic medical breakthroughs and improve health outcomes, including through a greater emphasis on prevention, leading to potentially huge savings on treatment.. The potential of big data, and what it means for policy-makers, if a key theme for OECD work in the next two years.

Third, the opposite side of the Big Data coin: micro-data. We’ve always tended to use averages and aggregates in policy-making – GDP per capita, average household income, and so on. Yet we’ve always known that the ‘average person’, or the ‘average household’, doesn’t actually exist or at least doesn’t represent the vast majority of the population. So why do we use it? Can’t we do better? While being mindful of data protection and privacy issues, the OECD Statistics Directorate has started to look at the potential of micro-data at the individual, family and firm level, to better understand why things happen the way they do, and therefore what policy responses could work best – for actual people, not the fictional average. Would a better understanding of firm-level data have helped prevent the financial crisis?

Finally, there is data-mining. The recent OECD Conference on Knowledge Based Capital noted the potential for new data-mining techniques to process qualitative evidence in the same way we currently process quantitative evidence (in the form of graphs and charts). This could have major implications for how we measure our policies and our societal well-being.

The ‘What Works’ Network in the UK, and these interesting new approaches to data at the OECD and elsewhere, provide some stimulating insights into how we can make better policy in these difficult times. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts, including if we can make connections between what is going on in the UK and similar initiatives around the world.

I guess another question is how normal people, rather than organisations like the OECD or government, can use this sort of power. There are lots of apps out there (I’ve been told). But also, how can people like teachers use evidence to improve impact? Ben Goldacre’s paper on building evidence into education is worth a look! http://media.education.gov.uk/assets/files/pdf/b/ben%20goldacre%20paper.pdf