14th January 2021 Vienna, Austria

Diplomatic lessons 4, Russia 1991-95: have a plan, and break it

Outside “The Two Chairmen”[1], the beer was cool and fresh.

My colleague raised his glass. ‘You had children a few years back,’ he said. ‘We can’t decide on the best time. What do you think?’

‘Some things, you can’t plan,’ I said.

I had met Pamela, a colleague in London, in 1990. Later that year, we sought a joint posting. Only three missions had two jobs coming free at our grade at the right time: Washington (too much like Whitehall, we decided); Brussels (too close to London); and Moscow.

Pamela already spoke Russian (and Chinese). I’d have to learn, having been told officially my language-learning skills were zero. She’d do the internal political job in Moscow. I’d do commercial. We applied, and were successful.

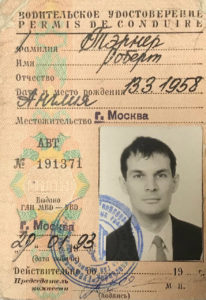

My Russian driving licence from December 1992. Official Soviet photographers had a way of making subjects appear rather, well, Soviet.

Then everything changed.

On 19 August 1991, Communist hard-liners launched a coup against Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, precipitating the collapse of the Soviet Union. I remember waking to hear a commentator on the BBC – none other than media tycoon Robert Maxwell – wondering whether Gorbachev was still alive. On 8 December the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus signed the Belovezha Accords, dissolving the Soviet Union and establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States. On my Russian language course we debated, over an atlas, whether we might end up posted to the CIS HQ in Minsk. This did not happen.

Pensioners dancing in Dzerzhinsky Park, spring 1993

My job in Moscow was abolished and I was reassigned to economic work.

In December we arrived in Moscow with our three-month-old son, Owen. On my first day, I watched a blood-red sun rise from our 13th floor flat in the Ulitsa Akademika Korolyova and set off to walk to the metro station through the snow. Our offices were in portacabins at the back of the old embassy, opposite the Kremlin.

To be a diplomat in Russia responsible for economic reporting for much of the Former Soviet Union[2] from 1992-95 was a privilege and a challenge. Life was tough for most Russians. Supermarkets and petrol stations were empty[3], healthcare was poor; hyperinflation and currency reform wiped out savings[4].

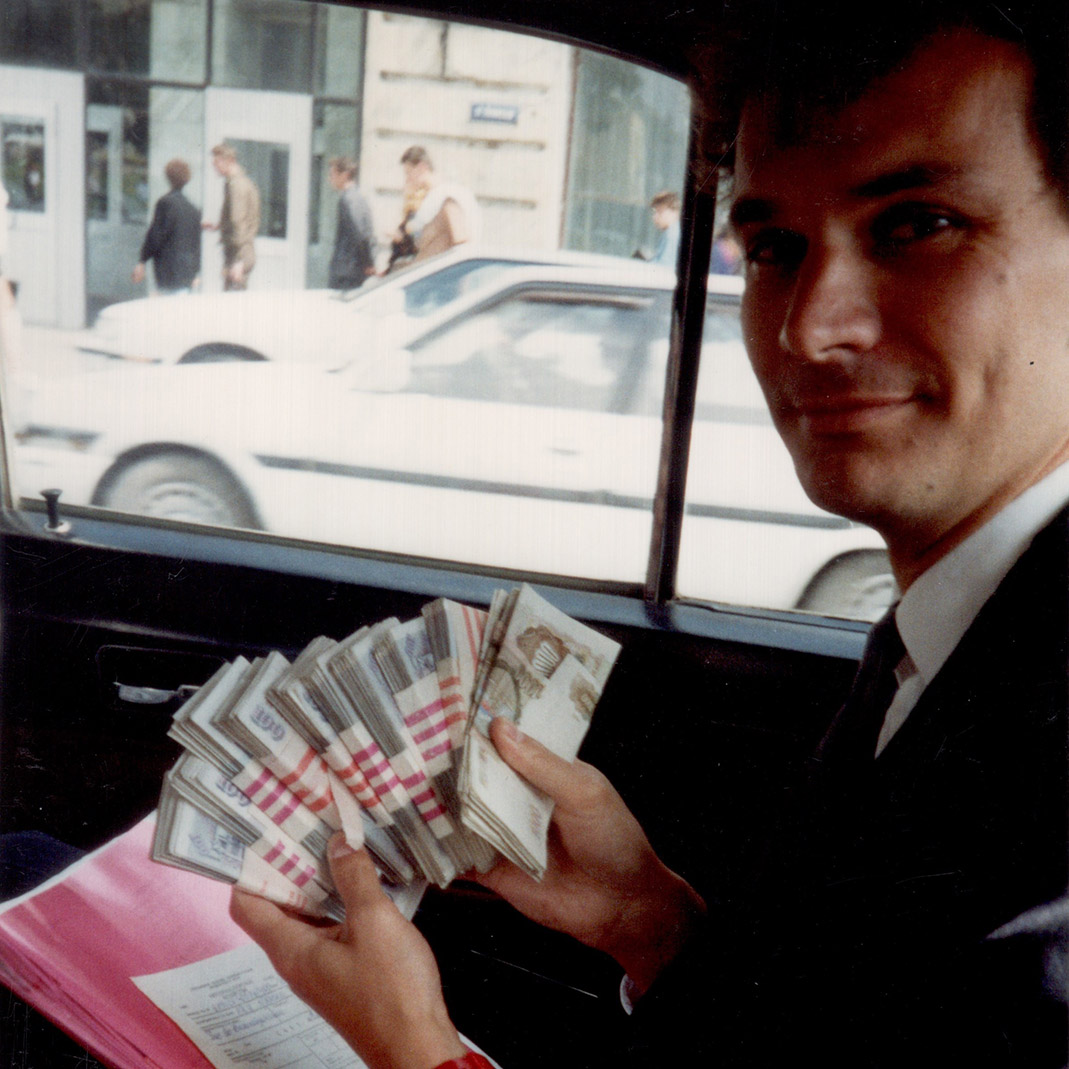

Hyperinflation: paying for a taxi in Vladivostok July 1993

With the country in turmoil, planning anything was fraught with complications. We had started our nine-month language course in 1991 learning Russian phrases such as “the inevitable collapse of capitalism”. By 1992 it was “the transition to a market economy”.

Enterprises faced particular challenges. A story at the time told of the engineers at a ballistic missile factory being summoned by the management and presented with a modern washing machine. ‘Here you go, lads,’ the manager said. ‘Make that.’ The manager of a private bank surprised me at a meeting by showing me a pistol he had bought to protect himself. Months later, he was murdered.

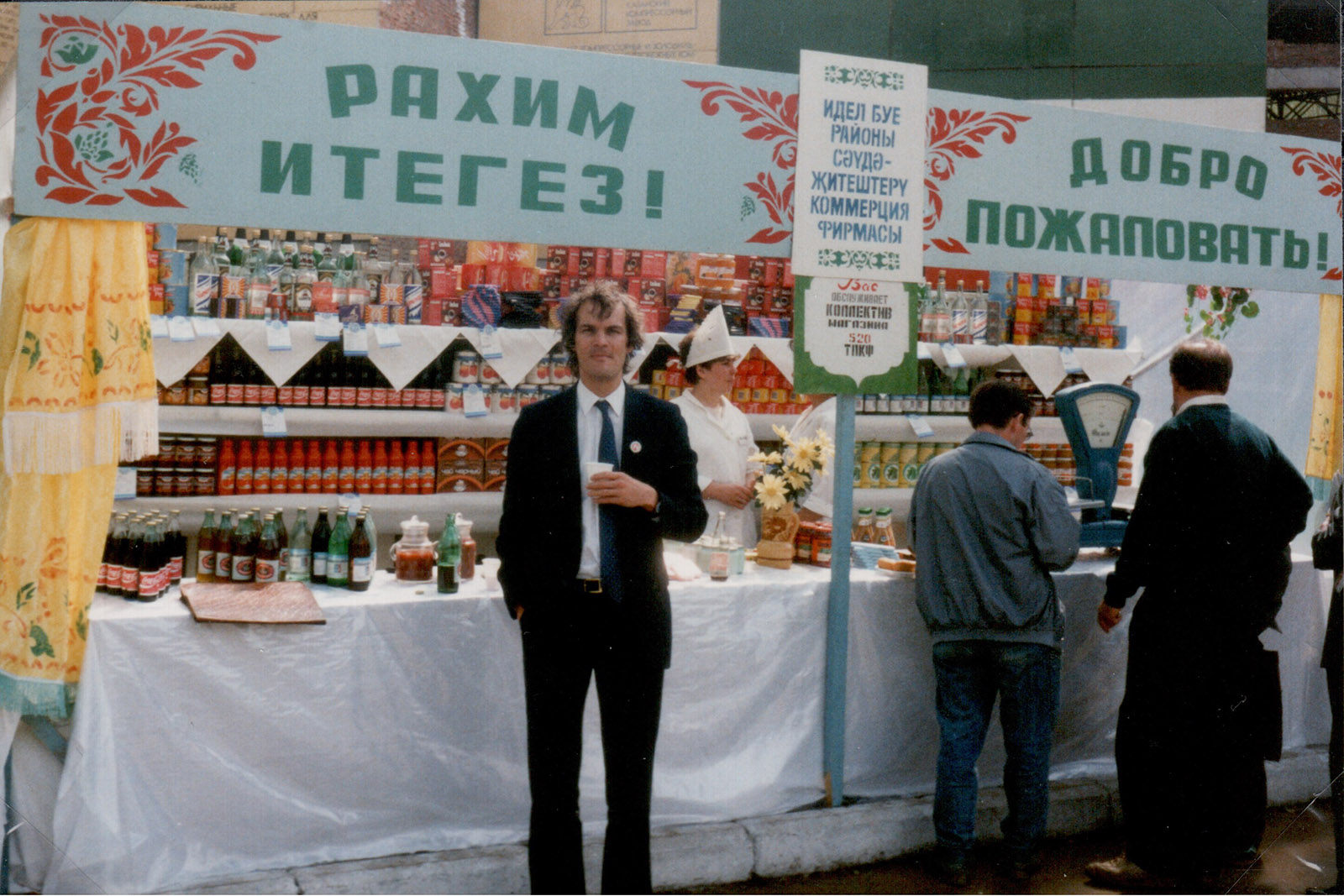

At an agricultural fair in Kazan, April 1994

Speaking Russian helped: few people outside Moscow spoke English. The job took me from Kaliningrad in the west to Petropavlosk-Kamchatsky and Vladivostok in the east. Everywhere, I met businesses, foreign investors and local and national officials seeking to establish order, or to make ends meet.

Although the uncertainty made any kind of planning tough, the Russians kept going. I saw pensioners at tea dances in the open air in Dzerzhinsky Park in the spring snow of 1993; youths erecting barricades on Tverskaya Street to resist the 3 October 1993 anti-Yeltsin putsch; and locals fishing from jagged ice floes on the coast of Sakhalin Island.

Tanks pass the Lenin Library in central Moscow during the October 1993 putsch

‘We have to adapt to the situation,’ a scientist said when I visited the Akademgorodok science park in Siberia. ‘If I drive 200 kilometres to pick mushrooms in the forest and my car breaks down, I can fix it. My US colleague on his way to the supermarket has to call a tow-truck.’

Vyazemsky, September 1995. My favourite stop on the Vladivostok-Khabarovsk section of the Trans-Siberian Railway was a chance to buy a Chinese beer

The key lesson of all this? Like the impressive Russians I met, who faced far greater challenges, a diplomat has to be prepared for uncertainty. It’s good to have a plan; but you must be prepared to break it if the right thing comes along. I didn’t foresee learning Russian; having two lovely children (Anna was born in 1994); or doing economic work in a newly capitalist country. All were unforgettable. All changed my life for the better.

‘OK, life is unpredictable,’ my friend at “The Two Chairmen” said. ‘So how do you plan the best time to have a child?’

‘It’s good to have a plan for all kinds of things,’ I said. ‘But sometimes you just have to ditch the plan and just do what seems right.’

*

The previous posts in this series are:

– Diplomatic lessons 1, 1979-83: Don’t judge a book by its cover

– Diplomatic lessons 2, 1983-87: Languages change everything

– Diplomatic lessons 3, 1987-91: go for the hard jobs

Coming up next: Diplomatic lessons 5, Hong Kong, 1995-98: make a difference

[1] A pub in central London

[2] The UK had embassies only in Kyiv, Baku, Almaty and Moscow – which covered the other post-Soviet republics

[3] We bought fuel from bowsers, usually run by Chechens, at the side of the road. Our first meal was a scraggy chicken bought from an elderly woman outside a metro station.

[4] In 1992 a Metro token cost 5 kopeks. By 1995 it had risen 100,000 times to 5,000 roubles.