16th June 2015 Colombo, Sri Lanka

800 years of the Magna Carta and Human Rights today

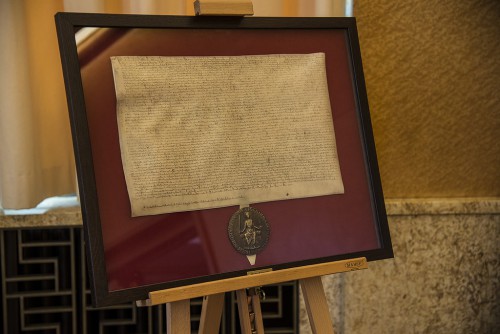

For centuries, the Magna Carta, signed by King John at Runnymede in England in 1215, has been quoted to help promote human rights and alleviate suffering all around the world. This week, we are celebrating its 800th anniversary, and its continuing relevance today. To mark the anniversary, my colleagues at the UK Mission in Geneva hosted a round table event with the International Service for Human Rights and international human rights defenders, to share experiences of promoting human rights in the the absence of rule of law. An important speaker was Ruki Fernando from Sri Lanka. He blogs below about how the Magna Carta spirit lives on through international human rights treaties but also public outrage at human rights violations.

“To me, the essence of the Magna Carta is limiting the sovereignty and powers of rulers, and moving towards reaffirmation of sovereignty and freedoms of the people. It is about rule of law, due process and equality of everyone before the law. This is particularly relevant to us in Sri Lanka today, as it was earlier this year that we as Sri Lankan people expressed our resistance to tyranny and reaffirmed our faith in rule of law and due process. But, like the Magna Carta, our victory is far from being complete.

The Magna Carta was not a gift from an oppressive ruler, but the result of resistance by persons who felt victimized by what they perceived as unjust rule. There have been other attempts to limit powers of rulers before the Magna Carta. But the Magna Carta has caught the imagination of those within and outside the UK, even till today. It was not just one document, but a process, during which the agreement that was the Magna Carta was withdrawn, discarded, openly flouted and fresh attempts made to revise and resurrect it. There would have been compromises as to the contents. This process is also part of the spirit of the Magna Carta.

At that time, the Magna Carta would have been revolutionary, with clauses such as “no free man shall be seized or imprisoned…except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land”. But it was was far from being perfect, with key clauses referring to “free men”, and restricting freedoms to women and peasants. It didn’t appear to have covered freedom of expression and religion.

Today, the spirit of the Magna Carta has gone beyond the shores of UK and found its way into modern day domestic and international human rights law, which has sought to affirm rights of all persons and communities. States have agreed on limits of state sovereignty to some extent through international human rights treaties and declarations, and mechanisms to monitor and report on implementation. International human rights treaties are perhaps advanced versions of the Magna Carta, where rulers have agreed what they should do and not do to people within their territories, whether their own citizens or non citizens.

The Magna Carta would have been an irritant to rulers of that day. Likewise, human rights appear to be an irritant to rulers today. This is probably why, as we try celebrate the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, some governments openly flout their legal, political and moral commitments and agreements towards human rights. At the domestic level and also international level.

These are ominous signs to continue the spirit of the Magna Carta. We should be careful about romanticizing the Magna Carta, which is a historical document and process, not a preventive or redress mechanism for victims of violations today. So today, we should look at the Magna Carta critically, recognize its limits, and focus on asserting its empowering and liberating spirit through a contemporary human rights culture. This includes legal and institutional frameworks at domestic and international level, with strong enforcement mechanisms. And importantly, a spirit of public outrage and resistance to tyranny of the powerful, whether it’s dictatorial and corrupt political leaders, brutal militant groups or exploitative economic forces.”

Ruki Fernando, 15th June 2015

Watch the British Library‘s film about the Magna Carta.

Thanks Ruki, and thanks for the blog! For those of you who aren’t following British politics closely right now, this comment relates to the Government’s intention to bring forward a British Bill of Rights, to replace the Human Rights Act. Britain has a long history of protecting human rights at home and standing up for those values abroad, from the Magna Carta on – not just since 1998. This commitment to human rights will not change and the UK will continue to help hold others to account for their human rights records, including Syria, South Sudan and Belarus. The future Bill of Rights will continue to protect fundamental human rights; what’s different about it is that it will aim to protect the system from the abuse it has suffered in recent years.

As 800 years of Magna Carta was being celebrated, exactly 800 years later, President Bashir of Sudan was allowed to leave South Africa, avoiding arrest for mass atrocities. The South African government appeared to have turned its back on its legal and moral obligations to execute the arrest warrant on Basheer from the International Criminal Court (ICC), which it’s own courts ruled was binding on them to implement. British friends of mine have expressed fear about withdrawal of the British Human Rights Act, and UK’s potential withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights, despite these having been a bulwark that has helped many victims of violations to seek redress. For example, this was the framework which had enabled the House of Lords to rule that the indefinite detention of foreign nationals was unlawful. On the day 800 years of Magna Carta was being celebrated, the UN High Commssioner for Human Rights, in his opening statement to the UN Human Rights Council expressed concern on this by saying “I am troubled by discussion of plans to scrap the United Kingdom’s Human Rights Act, and challenges to the vital role played by the European Court of Human Rights. I am worried by the impact of this initiative both in the UK and in other countries, including many where the UK is working to promote and protect human rights. As a long-standing democracy, the UK should set an example at home by ensuring that human rights protection, once brought in, is not subsequently weakened”.

These are just two examples of ominous signs to taking forward the spirit of the Magna Carta