30th November 2015

A famous Scot in the FCO for St Andrews Day

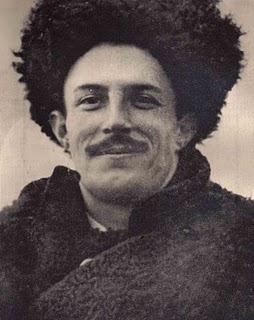

Sir Fitzroy Maclean (1911-96) — a ‘true Maclean scion’

‘A man of daring character, with Foreign Office training’: thus Winston Churchill perfectly summed up the glamorous and enigmatic Fitzroy Maclean, who combined the careers of diplomat, soldier, partisan, politician and writer. His talents — aided by personal charm and enviable contacts — enabled him to play an exceptional role during the Second World War. Widely believed to have been one of the models for his friend Ian Fleming’s creation James Bond, he also had something of the staunch gentlemanly bravery of John Buchan’s fictional hero Richard Hannay.

Born in Cairo into an old military family, and always proud of his Highland roots, Maclean nevertheless had a cosmopolitan upbringing, with a childhood in India and Italy as well as Scotland, which ensured a good knowledge of languages and wide cultural tastes. This predestined him for the Foreign Office, which he entered in 1933. After an enjoyable spell in Paris from 1934-37, he asked to be posted to the tougher climate of the USSR during the height of Stalin’s purges, which did not prevent him from undertaking dangerous solo travels to remote regions of the Eastern Soviet Union. His dispatches to Whitehall won him the reputation of a bold and clever young diplomat. However, back in London, service on the Russian desk pleased him less, and with the coming of war he decided to join the Cameron Highlanders, his father’s old regiment. Diplomats, however, were not allowed to enlist. Maclean showed a characteristic mixture of determination, ingenuity, and cheek: he stood for parliament (and to his surprise was subsequently elected), which required him to resign from the Foreign Office. He immediately volunteered for the Camerons as a private soldier, was promoted to lance-corporal, and was soon commissioned. He was posted to North Africa and joined the new SAS, whose early commando operations in the Western desert, for example against Benghazi, combined a high level of danger with a degree of black comedy. He moved on to Persia, commanding an almost entirely Scottish band of volunteers, one of whose exploits was the successful arrest — or kidnapping — of a pro-German Persian general.

This prepared him for his most famous and important mission. In 1943 he was chosen personally by Winston Churchill as ‘a daring ambassador-leader’ to be parachuted into German-occupied Yugoslavia as head of a small military mission (which for a time included Randolph Churchill and the novelist Evelyn Waugh) to the then largely unknown and mysterious Communist guerrilla leader ‘Tito’ — rumoured by some to be a woman, or perhaps even a committee. Maclean’s diplomatic and military skills were to be put to the test. The gentlemanly Scot and the Communist apparatchik Josip Broz (alias Tito) formed a good relationship, with Maclean developing an admiration for Tito’s military skill and courage. Maclean certainly played a part in the British decision to give full backing to the Communists, though he later insisted that Churchill had already made his mind up on military grounds. Nevertheless, Maclean, who had direct access to Churchill, certainly facilitated the process, and thus helped Tito to become leader of an independent postwar Yugoslavia able to stand up to Soviet pressure. Maclean remained until his death a friend of Yugoslavia, where he had a holiday villa.

After the war, Maclean continued his political career — or rather, began it, for during the war he had not occupied his seat in the Commons. He served as parliamentary under-secretary at the War Office from 1954-57. He made friends across party boundaries and — Tory though he was — maintained close contacts in Yugoslavia and the USSR, and was one of those who in the 1980s identified Mikhail Gorbachev as an important figure.

In 1949 he published a gripping account of his wartime experiences, Eastern Approaches, which made him something of a celebrity, and inspired future diplomats, for example Sir Ewen Fergusson, future Ambassador to South Africa and to France. It was followed by travel books, histories (including a History of Scotland), and biographies of Tito and of Bonnie Prince Charlie. He also put down firm roots in Scotland, for although always considering himself a thorough Scot, much of his life until this point had been lived elsewhere. In 1957 he and his wife (Lady Veronica, daughter of Lord Lovat) bought a house in Argyll, and he was elected Unionist MP for Bute and North Ayrshire (1959-1974). He died at the age of 85, having led an extraordinarily full and adventurous life. One of his wartime comrades thought that part of the explanation was his wish to be ‘a true Maclean scion … a big, bad Highland chieftain.’