21st October 2021 London, UK

Ignatius Sancho: changing perceptions of race in the 18th century

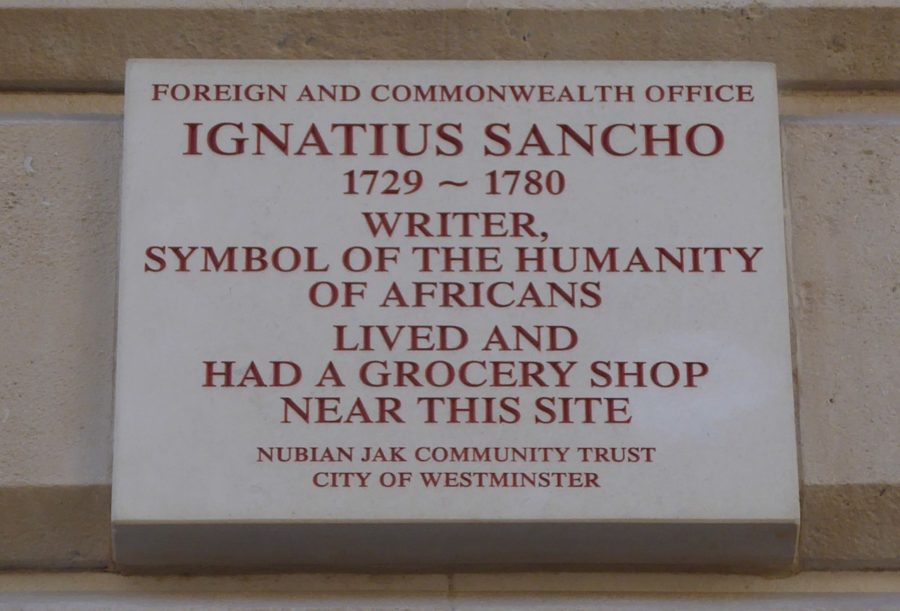

A few years ago, a plaque appeared on the side of the FCDO building in King Charles Street, Whitehall. Set high in the wall and easy to miss, it commemorates a former slave, abolitionist, writer, composer and grocer. Ignatius Sancho was a man who through his own authentic voice changed contemporary perceptions of what it was to be an African.

Details of Sancho’s early life are disputed. An early biography written by his near contemporary Joseph Jekyll was at least partially based on Sancho’s own account. This states that he was born in 1729 on board a slave ship bound for Cartagena, in the Spanish Colony of ’New Grenada’ (modern-day Colombia), where he was baptised. Sancho next appears in Greenwich as a child slave, probably in service to three sisters of the Earl of Dartmouth. He was then taken into the household of the Duke and Duchess of Montagu in the 1730s, where it seems his assertive and engaging personality was instrumental in obtaining his freedom.

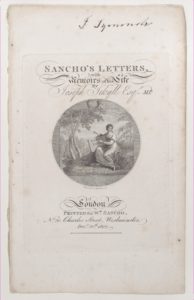

In his letters Sancho asserted that as a slave boy he was not educated to a high standard but later educated himself. He corresponded both with friends and with literary and cultural figures of the day, such as the novelist and cleric Lawrence Sterne. Sancho’s subject-matter ranged from domestic matters through to national politics including the sometimes-turbulent events in the country. Sancho’s letters were published two years after his death in 1780, along with Jekyll’s biography, and there were five editions by 1803. He is remembered as a first-hand witness to the anti-Catholic Gordon riots in London in 1780, where he penned a vivid blow-by-blow account of the breakdown of civic order. Adding to his literary output, Sancho was also the first black composer that we know of. In his lifetime he published four collections of songs and dances which would have been played in the elegant households of the time.

Following a period as butler to the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, it seems the Duchess paid Sancho an annuity with which he established himself as a grocer. He imported goods such as rum, sugar and tobacco – ironically, the produce of the very slavery he had escaped from. Sancho’s grocery business was located at No. 19 Charles Street (now King Charles Street), and the site is shown in a guide to the city entitled Modern London published in 1804 by Richard Phillips. No. 19 was at the corner with Crown Court, which would have led into the area now occupied by the central courtyard of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) London Headquarters building.

There is a further link between Sancho and the Foreign Office. He was one of 12,000 voters in the constituency of Westminster, and the first ever African recorded whose status entitled them to the vote at a time when most of the British population were excluded. In September 1780 he voted for the Whig politician Charles James Fox, a noted anti-slavery campaigner who became the first Foreign Secretary in 1782, a post he held on three occasions. Sancho’s example inspired the young Thomas Clarkson (born in 1760) to become a leading slavery abolitionist, along with Cambridge Vice-Chancellor Peter Peckard. Clarkson, Peckard and others hailed Sancho as an example of the common humanity and potential of those still shackled to that barbarous system.

That he obtained his freedom, educated himself and became a literary celebrity makes Sancho’s story extraordinary. That his voice has become known to us through his letters, music and a contemporary biography is remarkable, given that during his lifetime countless numbers of his fellow Africans disappeared into the brutal anonymity of slavery.