When we think about security in outer space, it’s tempting to fall back on tropes from science fiction or the movies – dramatic battles between space-suited soldiers in Moonraker, or powerful weapons threatening planets in Star Wars. In reality, there are threats to security and stability on Earth involving outer space, but they don’t include Death Stars.

The vast potential of space has been widely recognised since the dawn of the space age. Already in 1959 the UN set up a Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), in Vienna, which agreed a series of important conventions in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and last year adopted 21 guidelines for the long-term sustainability of outer space activities. The potential military uses of space featured in the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited nuclear tests in space, and the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which banned the placement of weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies. In the mid-1980s, the Conference on Disarmament and the UN General Assembly’s First Committee started discussions on ‘Preventing an Arms Race in Outer Space’ (PAROS), motivated by the prospect of conventional weapons being deployed in space. But because of the difficulty of effectively verifying the capabilities of objects in orbit, and because the discussions quickly became entangled in wider issues around ballistic missile defence, they have not made much progress.

As so often, developments have rather outpaced the UN process. The US and USSR were the only serious space powers in the 1970s. Today, up to 30 countries are active in space; many more have realistic ambitions to become space faring nations; and almost every country depends on space-based systems for communications and position, navigation and timing services such as the Global Positioning System. Importantly, those services are crucial for civilian life, as much as military operations, and it is civilian commercial operators, not states and militaries, who are the main drivers of the huge expansion in space activity. In an increasingly congested, contested and competed-in arena, the risk of misunderstanding or miscalculation between space actors is growing.

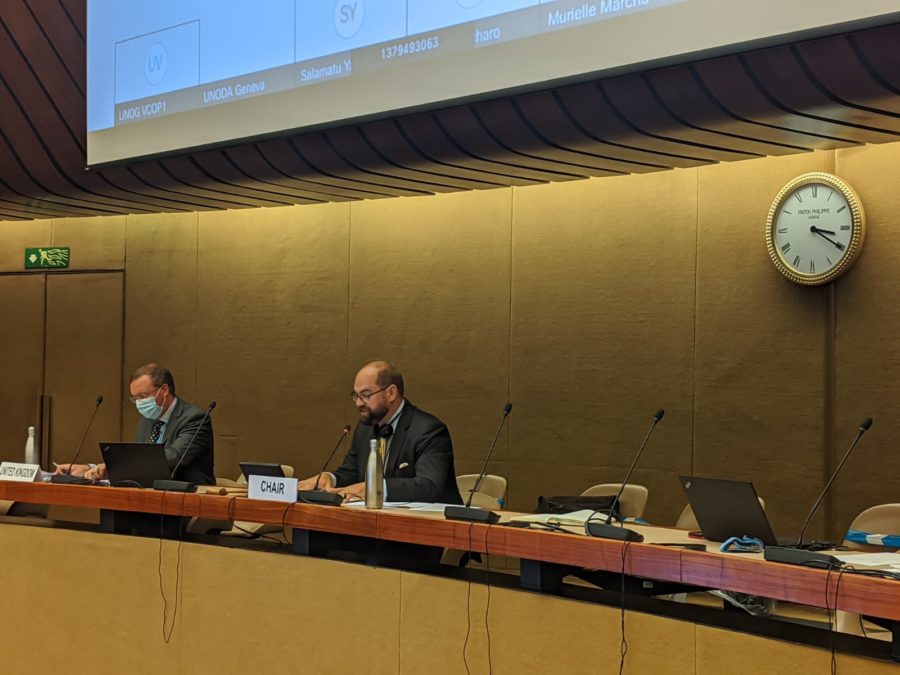

It’s apparent, then, that we need a new approach to space security: one that looks at the behaviours that might exacerbate tensions and drive competition, not just at military hardware. The UK will therefore table a draft resolution at this year’s UNGA First Committee launching a new discussion on reducing space threats through responsible behaviours, which I had the honour to present to the UN membership yesterday (26 August) here in Geneva. The draft resolution builds on discussions we’ve had with a wide range of countries, including through a series of regional conferences organised by Wilton Park, and proposes an open, inclusive, bottom-up approach to identifying responsible behaviour in outer space that would contribute to a lessening of tensions and a reduction of the incentives for arms racing. In our view, such an organic process, without a pre-determined solution, is the most realistic prospect for making progress, though of course it does not exclude any other existing or new proposals that others may have.

Proposing a new UNGA resolution in the current circumstances, with little prospect of being able to conduct the usual face-to-face negotiations in New York and no clear idea of how First Committee will work, is somewhat daunting. But I’ve been encouraged by the reaction so far, which shows that there is a growing understanding of the complexity of the security situation in space and a determination to find a way through the current deadlock. There’s a lot of work still to do, though – and passing the resolution will just be the beginning of what we hope will be a productive new process.