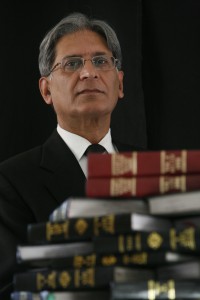

Guest blog by Senator Aitzaz Ahsan

Senator Aitzaz Ahsan, of Grays’ Inn Barrister-at-Law, is a senior lawyer, a veteran politician, a human rights’ activist, a constitutional theorist, a former political prisoner and federal minister, a left-wing campaigner against military regimes and a member of the Pakistan Peoples’ Party who currently serves as the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate of Pakistan. During prison terms he authored ‘The Indus Saga and Making of Pakistan’ a popular socio-political history of the origins of Pakistan. Ahsan completed his Law Tripos from Cambridge and is, today, an Honorary Fellow of Downing College, Cambridge. Ahsan is married to Bushra, a women’s rights campaigner. They have two daughters and a son.

A peasant woman enters the hot stuffy courtroom of the District Judge Gujrat in Pakistan. Her son has been taken by the police without charge. She is illiterate but knows that she can petition the judge under Section 491 of Pakistan’s Criminal Procedure Code seeking the remedy of “Habs-e-Baija” (Habeas Corpus: “Produce the body”). Article 77 of the Constitution of Pakistan simply provides that “No tax shall be levied for the purposes of the Federation except by or under the authority of an Act of Parliament”. During the full swing of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) against the military regime of General Zia, thousands courted arrest seeking elections to a sovereign Parliament. From 2007 to 2009 the lawyers of Pakistan spearheaded a mass movement in pursuit of due process of law and the independence of the judiciary. All these concepts had had their origin in the Magna Carta (the Great Charter) 800 years ago and 8,000 miles distant from Gujrat or the prison cells of Pakistan.

Habeas Corpus, Parliament, authorization of taxation by peoples’ representatives, due process and independent judiciaries are today household concepts, recognized as foundational to civilised societies. How many generations of freedom fighters, political activists, right’s movements across the world, have not focused their energies in pursuit of these rights and, having obtained them, for their protection?

The origins of habeas corpus lie in clause 39 of the Great Charter providing that: “No man shall be imprisoned…except … by the law of the land.” Independence of the judiciary emanated from clause 17 which separated the courts of justice from the royal court (“Ordinary lawsuits shall not follow the royal court around, but shall be held in a fixed place”) Integrity of the judicial process was buttressed by the royal commitment in clause 45 to “appoint as justices .. only men that know the law and are minded to keep it well”.

The origins of modern-day Parliament are found in clause 12 which provided that no “scutage” (tax) shall be imposed without “common counsel’ (not private advice). “Counsel” negated individual decision-making and also implied discussion and debate, crucial to any Parliament. Clause 14 emphasised that this “common counsel” was to be obtained by summoning the bishops and barons to assemble together. This assembly would eventually become Parliament. And, with a varying degree of effectiveness, Parliaments today oversee the governance of three-fourths of all mankind.

The Charter provided for diverse other matters as well, such as trial by jury; protection of widows’ interest (“A widow after the death of her husband shall forthwith and without difficulty have her marriage portion and inheritance; nor will she be forced to remarry”); and of property (“No Sherrif or bailiff of ours shall take horses and carts or wood of any freeman against his will”): for weights and measures (“There shall be one measure of wine and one measure of ale and of corn and one width of cloth in our whole realm”). Echoing the norms of times it also prescribed that “If one who has borrowed from the Jews die before the loan be repaid, it shall not bear interest as long as the heir is under age”.

This day, June 15, 2015 the bishops and barons, assembled in the field of Runnymede near Windsor, forced King John of England to sign the Magna Carta and to bind him and his successors down to certain concrete precepts of governance. Nowhere else in the Thirteenth Century world, or in later centuries, could this have been possible.

But little did its authors, the rugged barons and the rustic bishops, know that its key principles would, in the fullness of time, be adopted by a variety of nations across the world. Nor indeed do most beneficiaries, such as the peasant mother or many a political prisoner, know the roots of the remedies and rights she or they pursued. The spread of the Great Charter has been seamless and imperceptible. Yet its principles today span the globe. The sun may have set on the British Empire, but it continues, at all times, to shine on some part of the planet that is under the sway of the Magna Carta.