As part of the UK Science and Innovation Network I get to work on some pretty cool stuff; a colleague once described my job as “nerd in residence”. Working on space research collaboration is definitely a highlight; and when I heard that the world’s largest space conference was coming to Australia, I jumped at the chance to attend.

The 2017 International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide attracted over 4,000 delegates, including space entrepreneur Elon Musk, science communicator Bill Nye, several astronauts and the heads of global space agencies. The UK was well represented, with delegates from the UK Space Agency, Surrey Satellite Technologies, Elecnor Deimos, Reaction Engines, and a number of British scientists presenting papers.

I was thrilled to be part of the crowd – even if I narrowly avoided being run over by a Mars rover while taking a selfie.

As with many aspects of the UK-Australia relationship, our cooperation on space goes back a long way. In 1966, the UK and Australia were involved in a US-led programme known as SPARTA, which aimed to investigate the physics of missile re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere. It was a spare rocket from this project that launched Australia’s first ever satellite, WRESAT, from the Woomera test range in South Australia almost exactly 50 years ago.

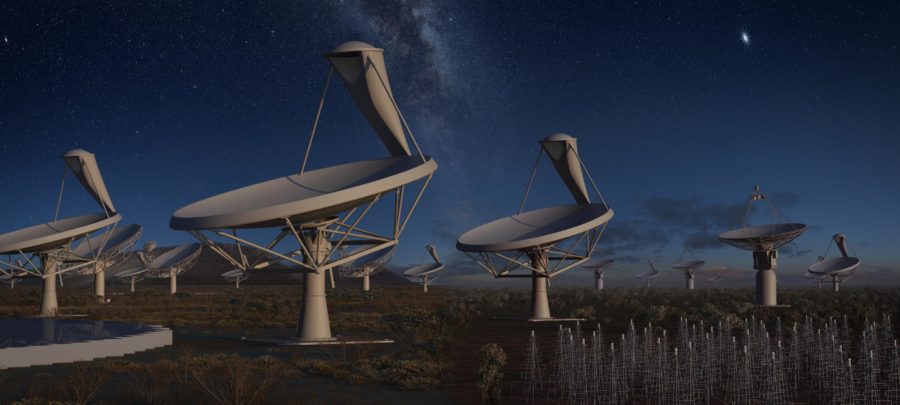

More recently, the UK and Australia have been working together on the Square Kilometre Array radio telescope, which will have installations in Australia and South Africa and its headquarters in Manchester. One of this century’s most ambitious science projects, the SKA will be the world’s largest scientific instrument, imaging huge areas of the sky.

The Australian government’s announcement that it will establish its own space agency created a huge buzz; it also opened up new avenues for cooperation. Australia has already taken a big step to increase its data-gathering capabilities; public research agency CSIRO signed an agreement in Adelaide to become a launch partner in the UK’s sophisticated NovaSAR satellite.

NovaSAR was built by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL), backed by a £21 million grant from the UK Space Agency. SAR stands for Synthetic Aperture Radar; this advanced radar technology can pick up light wavelengths that aren’t visible to the human eye. Although a small, low-cost satellite, NovaSAR outperforms traditional satellites in that it can capture images of the earth and sea in all weathers and even in darkness.

L-R: UK Space Agency CEO Graham Turnock, CSIRO CEO Dr Larry Marshall, British Consul-General Chris Holtby, CSIRO CSIRO’s Executive Director Digital, National Facilities & Collections, David Williams, and SSTL Commercial Director Luis Gomes

CSIRO’s investment in NovaSAR means the agency can direct the satellite to collect data over Australia and South East Asia. It has important implications for disaster management; where it currently takes up to 12 hours to access images of disaster areas, NovaSAR will cut this time to around 60 minutes. This is particularly relevant for Australia when it comes to monitoring floods and bushfires. NovaSAR data can also be used in a range of other areas, including weather forecasting, climate and water cycle modelling, land use monitoring, forestry and conservation management, carbon accounting, maritime policing, and mapping waterways, coastal habitats and coral reefs.

Projects like this are why we invest in space. As Nobel Prize winner and Australian National University vice-chancellor Brian Schmidt pointed out at the conference, there is enormous public good to be found in the space industry. Satellites are crucial for communications, land and water management, long-term weather predictions and even wine-making. They can help monitor climate threats and the spread of infectious diseases. And in my case, they help avoid getting lost on the way to the Adelaide Convention Centre.

NovaSAR is due to launch later this year. It’s a small satellite, but with big implications for space-related research, and for UK-Australia collaboration.