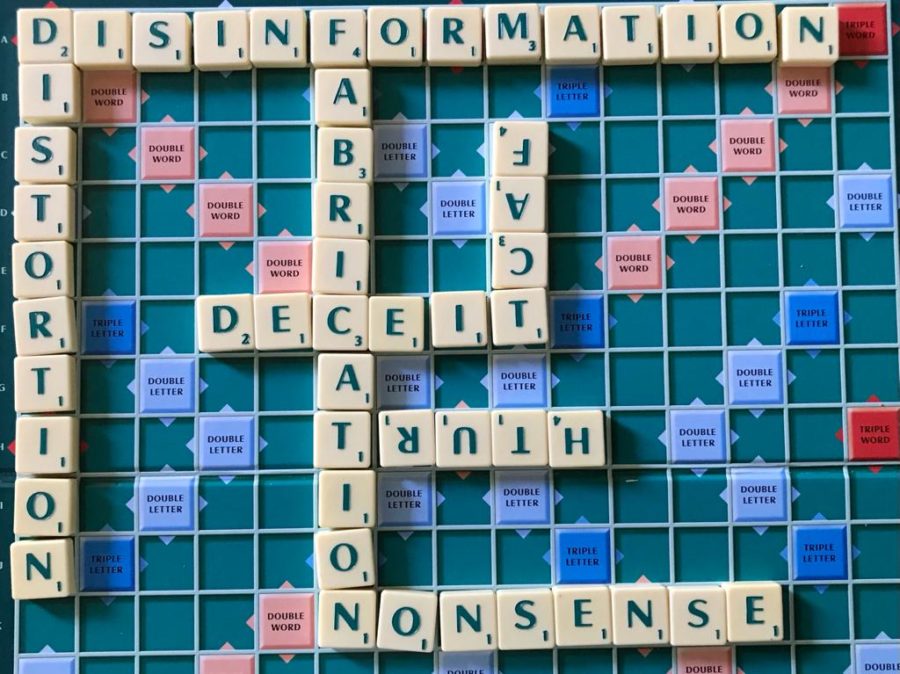

Disinformation has become one of the defining words of our age. It is not a new phenomenon. But its present scale is unprecedented, helped by round the clock broadcasting and social media.

There is a shorter word for it: lies. But ‘disinformation’ perhaps better conveys the sense of deliberate corrupting of the media environment with fabricated information in order to influence (or frighten) a target audience.

Disinformation is like a poison designed to seep through the veins of society. Those who fabricate and spread it do so hoping that readers will be ignorant of the facts, unable to tell fact from fiction, or simply confused. We will never know how many pandemic deaths were due to anti-vaccine disinformation.

Putin’s disinformation machine is multilayered. At the top are big lies about ‘liberation’ of a sovereign state and ‘denazification’ of an elected Government and (Jewish) President. Beneath this, propaganda channels push multiple versions of the ‘truth’ and promote fake ‘experts’. (In the month after the Salisbury Novichok attack Russia Today and Sputnik alone put out over 100 different and contradictory narratives.) At the bottom sits a troll army scribbling social media abuse and illiterate comments under foreign newspaper articles.

Much of Moscow’s current effort is focused on keeping the truth of the war from the Russian people. It is learning that this truth is hard to hide, whether it concerns war crimes, military casualties or warships on fire.

Media freedom is a fundamental pillar of democratic society. But media freedom does not mean a right to make up and publish lies. The International Federation of Journalists Global Charter of Ethics says that the first duty of a journalist is respect for the facts and for the right of the public to truth. Likewise, the Serbian Journalists’ Code says journalists have an obligation to report events accurately, fully and in timely fashion, taking into account the right of the public to know the truth.

According to the Serbian code, journalists should confirm the accuracy of their reporting. It surprises me that some Serbian media never call to verify information before publication or broadcasting. A quick check could avoid publication of accidental error and fabricated rubbish. After all, this is deception aimed at the Serbian public and reputational damage risked by the Serbian media.

The best protection for us all as consumers to to read and listen critically. We can ask ourselves whether information is credible. Where did it come from? Was it checked and corroborated? Can this source or outlet be relied on?

If the answer is ‘no’, the best thing to do with disinformation and propaganda articles is to use as a wrapper for fish and chips (or a cone for sunflower seeds).

This article first appeared in Serbian Blic daily on 30 April 2022.