This article is part of a series of guest blogs contributed by Brits who have lived and worked in Laos, or who have other interesting links to Laos.

In 1972 my father was posted to Laos as 1st Secretary (Aid), his first posting (he had joined the Foreign Office relatively late from academia: one of a number of late entrants from a scientific background recruited to add some intellectual leavening to the arts-dominated FCO). I was 6 at the time, and spent the following two years in Vientiane.

We had left Scotland a couple of years previously, which had been a big change, but nothing compared to the culture shock of Laos.

My overwhelming memories of Laos are vivid colours, heat, pungent smells and dust. We lived in a house on stilts (concrete not wooden), and in the dry season the river Mekong – unimaginably huge and sluggishly brown – was at the bottom of our garden, while in the wet season the garden was at the bottom of the river.

During the dry season we spent a lot of time in the garden and under the house, which harboured a bewildering variety of insects. We had a mango tree and when they were in season we children gorged ourselves (and I fully agree with those who say that the only place to eat a ripe mango is in the bath).

The garden was also home to some geese (excellent guard dogs who reared and hissed at anyone they didn’t know. And even some people they did know) and ducks. I guess they all managed fine in the wet season.

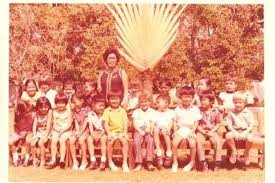

School was at the somewhat grandly named Lao International school. This was a time when the Lao Royal Family was still in power, and one or two of the Lao Princesses were class mates (I think there were quite a lot of Princesses). The photo of our class was taken in June 1972 – I’m top right.

I had no idea what people in the Embassy did, of course, but the key photo shows the top management team in uniformed splendour (my father is on the right. Sideburns were clearly de rigeur in 1972). I remember vividly that the Embassy had a twin engine Beaver aircraft, flown by the Defence Attache.

I remember sitting in it on the ground but never in the air. But we did often use the Embassy boat to motor up and down the Mekong at weekends. Most spectacularly the boat was a vantage point for the annual rocket festival, which heralded the start of the rainy season.

The rockets were big bamboo tubes filled with gunpowder, with amazing decorations, which flew one by one from a large bamboo stand specially built for the occasion. I use the word ‘flew’ loosely here: most leapt skywards and then plunged into the Mekong, and in our second year the rocket stand itself collapsed into the river. It didn’t seem to stop people enjoying the occasion.

Laos was so far from the UK, and travel so expensive, that I don’t recall anyone from the UK visiting us. We adapted very much to local food, but I do remember every now and again we would get a shipment from somewhere, and unpacking was a real highlight, with cornflakes back on the menu at least temporarily.

There was no fresh milk to be had, and after two years of powdered milk I couldn’t stomach fresh milk for a long time after we left Laos. For a while we bought ice lollies from a vendor at the end of the road until we were direly warned never to buy from there as they were made from river water. I don’t remember ever being ill, though there was a lot of illness around.

And forward nearly 40 years… Last year I was fortunate enough to visit to assess the need for consular resources and to meet the Lao authorities and the Australians, who had been kindly looking after our consular interests since the Embassy closed.

Vientiane seemed oddly familiar, but I remembered it as a huge place, whereas actually it’s rather small. The Residence was still in use as the Australian Residence, but our old house had been demolished as part of the anti-flooding work on the banks of the Mekong.

The old market is the same, but is crammed with stalls selling white goods rather than fish, meat and veg. And it was a poignant moment for me going to a meeting in the MFA as my late father must have done many times (I suspect it hasn’t changed much, physically). The Lao people themselves were as friendly as I remember.

The currency in the 1970s was the Kip. One of the things that had impressed the schoolboy me most was the fact that they had no coins (and they still don’t – a useful fact for any pub quizzes – I think it may be the only country where this is the case). There were notes from 1 Kip to many thousands. Catching sight of some old notes in a shop window I bought some as souvenirs.

It turned out the shopkeeper, who was of Indian origin, was my own age exactly and had lived his whole life in Vientiane. We talked for a while about Laos and its history, and what life had been like for him over the time since I left. In many ways it had been a very difficult time, and he was happy that we were establishing an Embassy in Laos after such a long absence, as I am.

I enjoyed life there immensely, and it will be an amazing posting for those fortunate enough to go there.