Today saw the launch of a very significant new initiative by the OECD and WTO, called Trade in Value Added, or TiVA. Why is it attracting so much attention? Don’t we already have statistics on trade?

We do, but the the way we’ve looked at trade statistics for years no longer necessarily reflects the way we produce and exchange things today.

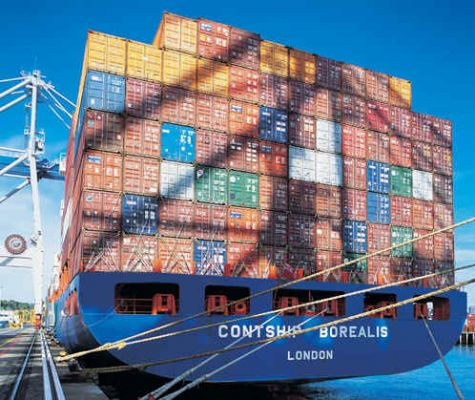

A product isn’t just made in one country and sold to another. Rather there is a chain, with a number of different countries each adding something, both tangibles such as components, or services such as design or computer code.

So the value added by an exporting country is likely to be much less than the total value of the product.

The new TiVA database will require further honing and expansion but for now it takes data from 40 countries and 17 sectors and illustrates the reality of global value chains. Take the following commonly-discussed trade phenomena:

The Airbus Effect: The UK builds Airbus wings, and sends them to France for final assembly before the whole plane is exported to China. Traditional trade statistics show the value of the wings as UK exports to France, and the entire value of the plane as a French export to China. Whereas TiVA would show the wings as a UK export to China, and the French export to China would exclude the value of the wings – overall a better picture of who has done what, but also of where the UK’s final markets are.

The i-Phone Effect: i-Phones are assembled in China using imported components and intellectual property, and then exported to the US (and elsewhere). Traditional trade statistics count the total value of the i-Phone as a Chinese export to the US. TiVA isolates the value added by China from the imported content (some of which come from the US). The overall effect across the whole system is 25% reduction in the Chinese trade surplus with the US, but also a shift for the US from 3rd to 2nd largest exporter to China.

The Rotterdam Effect: Many goods pass through Rotterdam before re-export. Traditional data therefore gives very high figures for exports to and imports from the Netherlands. However the TiVA methodology, by looking rather at where final demand lies, overcomes this distortion in the data.

A key conclusion coming from all this is that attracting imports is as important as boosting exports – the competitiveness of the latter relies to a significant extent on the competitiveness of the former.

Pascal Lamy, WTO Director General, noted at the press conference that this data should help spell the death of mercantilism – the belief that imports are bad and exports are good. Indeed, the OECD suggests that a country could gain even from unilaterally removing barriers to imports of intermediate goods or services.

Thanks to TiVA, our measurement techniques are slowly catching up with the reality of global trade, and can help us change the terms of the debate on trade, including making progress on global trade negotiations.

The UK will certainly be trying to get the policy message across during its G8 Presidency in 2013, and as a member of the EU and G20.