The death of the last northern white male rhino Sudan on March 19 in Kenya sent the world into mourning. When Sudan was born in South Sudan in 1972 there were around 1,000 northern white rhinos left in the wild. Now there are only two left, both females.

Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson called the death “an utter tragedy.”

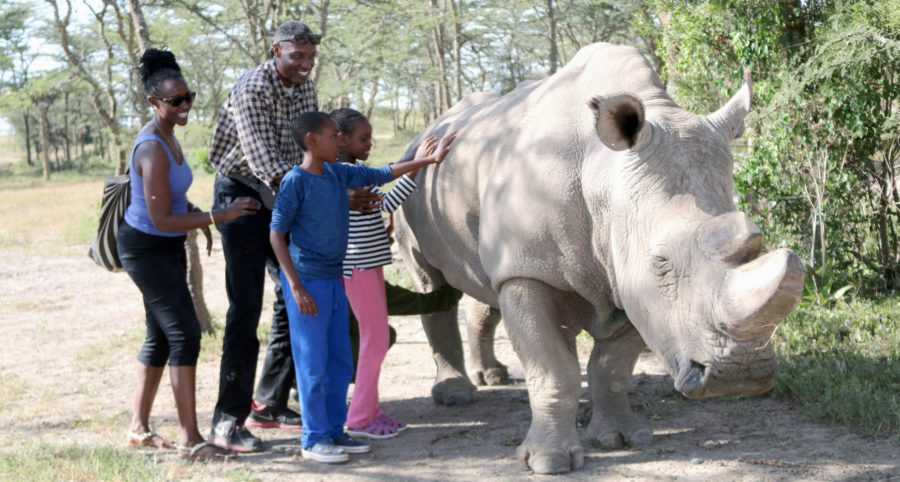

Kaddu Sebunya, the president of the African Wildlife Foundation, took his children to see Sudan in 2016. He speaks of his sorrow – and his hopes that Sudan’s death could change the conversation around conservation. This is a priority for the UK, which is hosting a global conference on the illegal wildlife trade in October 2018.

Our interview with Kaddu Sebunya:

How well was Sudan when you saw him?

When I visited the rhino sanctuary at Ol Pejeta Conservancy with my daughter and son, we were struck by the playfulness of the young rhinos and the majesty of Sudan, the patriarch. The guide told my children that Sudan was the last male standing. Born in the wild, captured and taken to the Czech Republic, he was then relocated to Ol Pejeta Conservancy. He spoke of the challenges of procreation for the old rhino. This was too much information for my children to process.

They turned to me with questions – why is Sudan here and not back to the wild? Why was he taken to the Czech Republic? What is extinction? Why are the rhinos guarded 24 hours? My answers only attracted more questions. How did we get to the point of extinction?

How do you explain to children that this was a result of human greed, negligence, lack of understanding of our connectedness to nature and ignorance of wildlife’s contribution to our survival as Africans?

How much has Sudan’s death affected you and those you work with?

AWF Chief Scientist Dr Philip Muruthi sent me a WhatsApp message breaking the news. I was saddened. Sudan’s very public death, captured and archived minute by minute on social media for more than a month, was a painful metaphor of failure in conservation.

It is not only rhinos that we are losing. Lion poaching has reduced the continental population by half from 50,000 in 2005 to an estimated 23,000 today. Sudan’s death brings out the urgency for Africa to decide the role of wildlife and wildlands in a modern continent. We must negotiate how we want to live with wildlife and the space we need to set aside.

Were you surprised by the reaction in Africa to Sudan’s passing?

In decades working on conservation, I have rarely seen this kind of outpouring grief for a wild animal. This time there was a sense of mortification that something horrible had happened. Sudan’s death is probably the first time that young Africans have confronted extinction in their lifetime as something real, not as history or a story in a Discovery Channel documentary.

Do you think Sudan’s death will inspire more leaders in Africa to fight for the preservation of endangered wildlife species?

The death of Sudan has been felt to be a proxy for wider African governance failure and of the reality of environmental existential threats.

There’s a chance that African countries will include wildlife and wild-lands in their blueprints for socio-economic development. But this will not succeed without legitimate discussion among African leaders about the role and place of wildlife and wild lands in modern Africa.

Could Sudan’s death be a turning point in conservation for the continent?

Sudan’s death provides important lessons for future conservation successes in Africa. The focus on the resources spent to protect Sudan and the efforts to use IVF and stem cell science to save it from extinction has understandably sparked questions whether that was the best use of resources in places where most people have no healthcare to speak of.

But this could be a turning point because social media shows us that young people were particularly moved and agitated. There is a new large constituency that can be rallied to help engineer a conservation turnaround in Africa.

Have your say:

What were your thoughts on Sudan’s death? What more should be done to change the conversation about conservation in Africa?