For me, one of the joys of diplomacy is the opportunity to really get to know other countries and cultures. Understanding the local language helps me do that. It also helps others get to know and understand me, and the UK. It allows a personal connection. As Nelson Mandela said:

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart.”

I’m learning Tagalog at the moment, before starting work as Ambassador to the Philippines in August.

My background is in languages. I was lucky enough to develop a knack for French at school which continued through to university. Speaking French was invaluable during my two postings to the EU in Brussels as it allowed me to negotiate with my colleagues more effectively when French was their preferred language. The FCO taught me Thai when I was in Bangkok and Spanish when I was in Madrid. I’m sure I did a better job in both countries as a result.

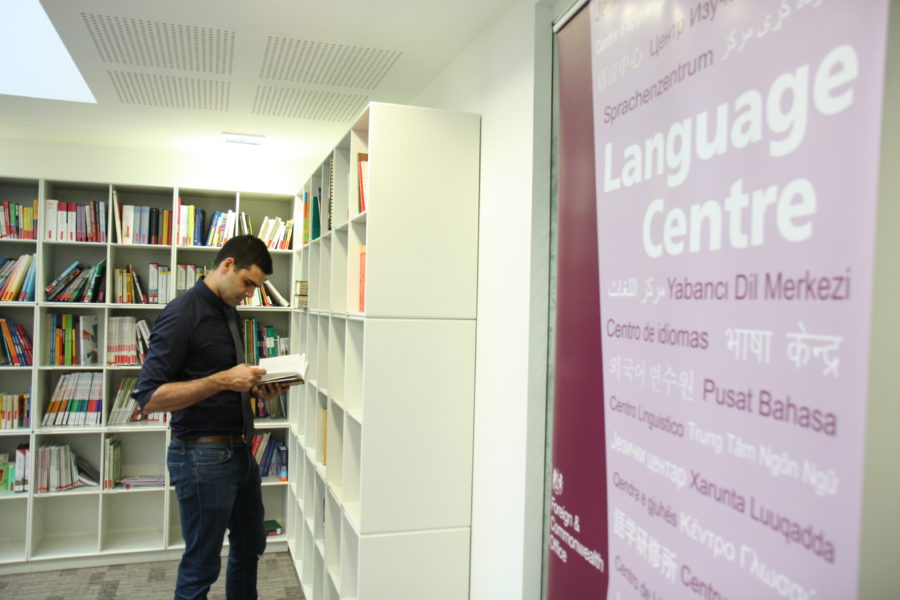

The FCO recognises the importance of language skills. It has its own language teaching centre in the basement of its King Charles Street HQ. Every year over 200 hundred of us beaver away trying to master a variety of languages, from Albanian to Zulu. Around the world the FCO has over 500 “speaker slots”, where the person in the job is expected to be proficient in the local language.

While studying a language may at first sound like a welcome alternative to the daily grind of office life it’s no picnic. Rightly so. This is a core professional skill and we have to take it seriously. Typically we have tuition for 15 hours a week, and on average around 20 hours of homework every week. We have regular tests, assessing our progress against the internationally recognised Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Some of us spend an extended period of “immersion” in-country where we speak nothing but the language we are learning. And then, when we are ready, we take our formal exams usually at C1 (“Operational”) or C2 (“Extensive”) level. Passing means we are ready to live and work, with comfort, in that language. The whole process is brisk. I’ve got 18 months to get to C1 Tagalog (compared to the 11 years I had to learn decent French!).

On top of that we use radio, TV, newspapers and social media to expand our knowledge, and to help bring the language to life. And that, for me, is the key to learning any language. Dry grammar is essential. I’m struggling at the moment with the difference between actor-focus and object-focus conjugations in Tagalog. I’m afraid there’s no alternative to plugging away, learning the rules and practise, practise, practise. But, alongside the grammar, I learn most effectively when my lessons relate to what I do in my life. Diplomats need to be able to operate in a range of registers: social chit-chat alongside political discussion; day-to-day practicalities alongside macroeconomics. We need to be able to discuss climate change as effectively as we can book a doctor’s appointment. Building capability in these and other areas has to be part of an effective “language journey”. Connecting the language to your life makes it real, and helps you learn.

Confidence is also important. You have to take the plunge and try to express yourself. At first it’s always embarrassingly slow and often wrong. But we all need to stick at it. As your confidence builds, what was difficult becomes easy. And nothing beats the thrill of being understood in a foreign language.

The practical benefits are enormous. People are more likely to be willing to see you if they know they can speak to you in their own language (and access and influence are everything for a diplomat). And they’ll speak more comfortably if you know enough of their language to put them at ease. Your media work (traditional and social) will reach more people if it is in their idiom. You will be able to speak directly to a broader range of people right across the country. And in today’s fast-paced world you save precious minutes if you can grasp an official text or piece of news in the local language rather than having to wait for someone else to translate it. The ultimate prize, if your level is good enough, is to be able to spot the subtleties of language that give you an insight into how someone is thinking: why they chose the formal rather than the colloquial; why they opted for the traditional noun rather than its more modern equivalent.

And in the middle of all of this is an exciting voyage of discovery, as you navigate your way through a new landscape, happening upon wonderful words along the way. My personal favourite in Tagalog at the moment is “pinakamakapangyarihan”, meaning “the most powerful”.

But, above all, language helps you really understand the country where you are serving. My Tagalog grammar book says:

“When an English speaker learns Tagalog, he should learn more than how to say, in a new way, something he has always said in his old language. He learns, or should learn, to look at life from a point of view different to the one he has always had.”

I think that’s spot on.

I’ve still got a long way to go in my latest linguistic adventure but do have a look at this 30-second video if you want a sense of how far I’ve got (and any tips to help me improve would be gratefully received!).